The Family Museum has the ambition to become an international archive (A), research (R) project and collaborative (C) hub (ARC) for those active and interested in the field of vernacular family photography.

We are currently looking at ways to digitise our collection, which comprises thousands of film photographs and negatives, photo albums, vintage cameras and photographic materials and objects. As we progress, images and albums will be viewable on our Archive and Blog pages.

In 2019, we held our launch exhibition, Auto-Memento, and published the first issue of our found photography zine, Famzine, which features contributions by artists, historians and collectors working in this area of visual culture. Issue one is now sold out but can be viewed on our Issuu page here: Famzine.

Below, as part of our ARC initiative, we feature book reviews and interviews with artists and curators who we’ve met on the incredible journey that is exploring the world of family photography.

La Damnation de Faust

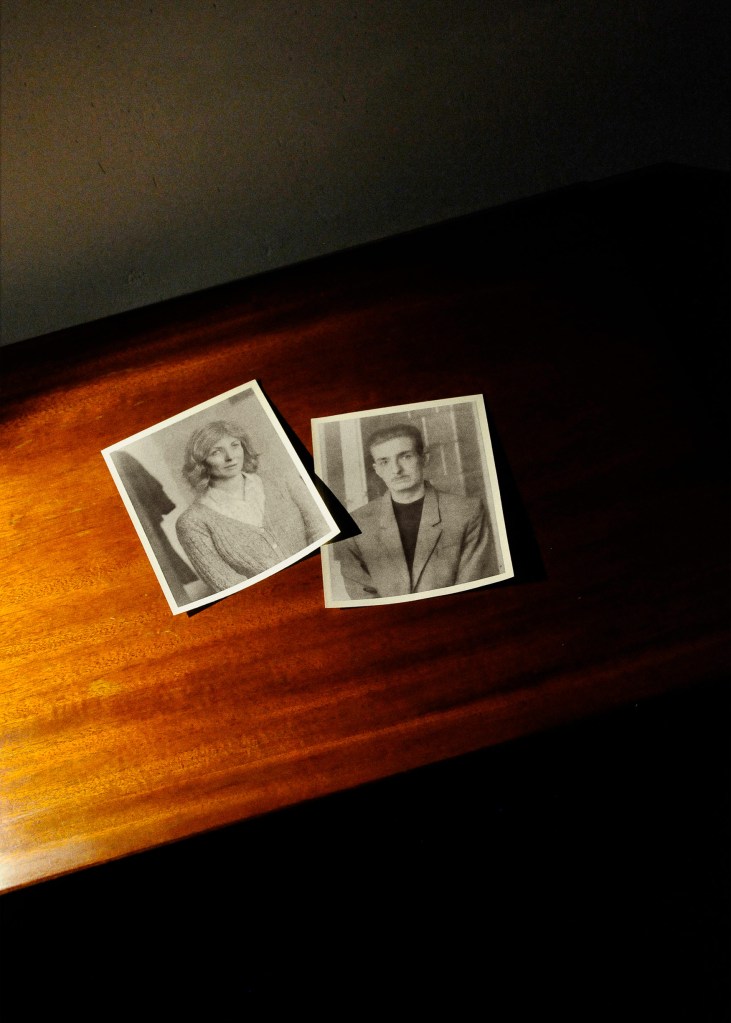

Recently The Family Museum had the pleasure and privilege of collaborating on Berlioz’s operatic interpretation of La Damnation de Faust by Eduard Goethe at the Théâtre de Champ Élysées in Paris.

Co-director Sylvia Costa, recipient of L’ordre Chevalier des Arts et des Lettres, contacted us with a request to use images from The Family Museum archive for projection during the performance. After a few weeks of back and forth we were able to find images ideal for the scene she had in mind. Sylvia is noted for using ‘every artistic medium to conduct her exploration of theatre’, including, on this occasion, the humble family photo.

The Family Museum attended the premier on 3rd November 2025, and a thoroughly enjoyable and rewarding evening was had by all.

The Archive as an Unfinished Project

Interview with Cassia Clarke by Amouraé Bhola-Chin

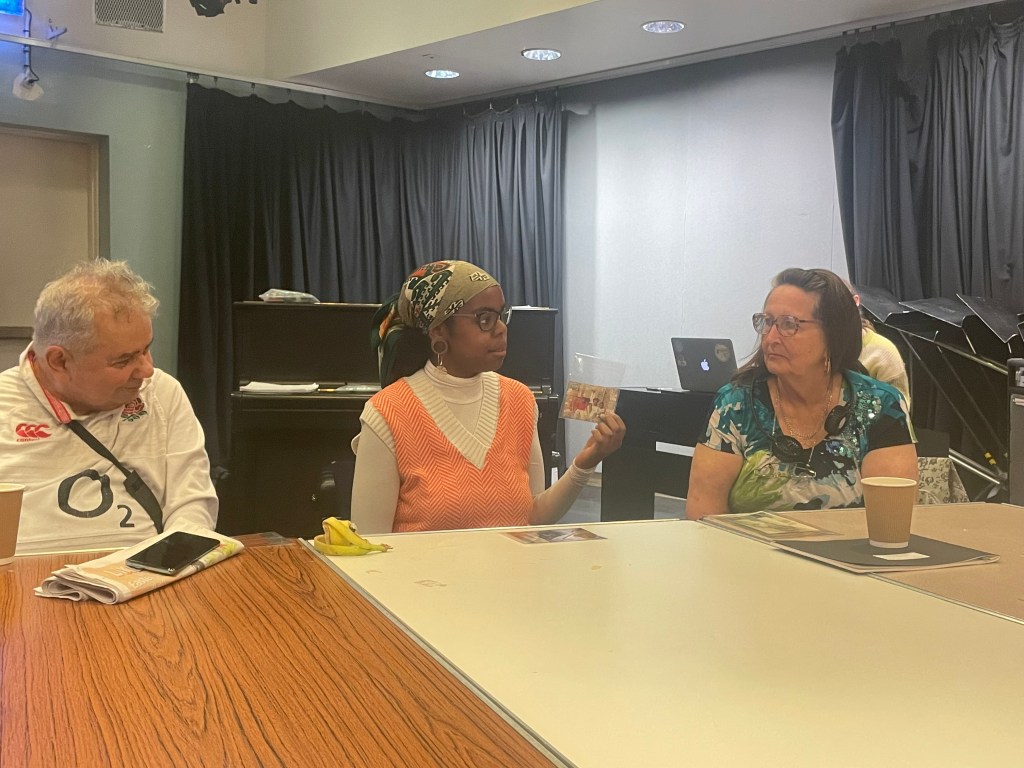

Amouraé and Cassia met on the Young Archivists 2023 course run by Pawlet Brookes at Serendipity Institute for Black Arts and Heritage, which took place between Leicester and London. Being inspired by Cassia’s practice, Amouraé wanted to question her in the hope to inspire others to experiment with the meanings and use of their own collections.

Amouraé Bhola-Chin: I know you lead workshops with groups regarding the legacies of family photographs. As a self-taught archivist, what challenges do you face when sharing your experiences with others?

Cassia Clarke: As I am not formally educated in archiving or conservation, I have faced many challenges, and my greatest challenge has been myself – overcoming my self-doubt and imposter syndrome. When I make initial contact with established archival institutions or professionals, I am hyper aware of my self-taught status, and I feel this great need to prove my intellect in the field. I have this overwhelming fear of being perceived as stupid, so I end up overextending myself in many situations when forming these new relationships. By the end of these meetings, I am wholeheartedly welcomed by these places and people as they are more than happy to not only engage with me, but to provide ongoing support. Many have shown great interest in the fact that I am self-taught, and how far I have progressed independently.

Amouraé: In your work, you mention our failure to record. Whilst reflecting on family photographs in the ‘Honour Thy— Archiving to Remember’ workshop that I attended in April 2024, you got participants to respond to the emotions the canon and archives ignore. What was your hope behind this?

Cassia: During the Streetwise Opera workshop, we had a conversation about value. What does it mean and who determines that value? Upon reflection of the workshop, I wanted to unpack that word – its meaning, its impact, and implications. I felt that value, in the context of domestic archives, could be distilled into a handful of parts: historical, identity, interpersonal connectivity, therapeutic, and emotional – although I should mention that this list is personal and not exhaustive.

It was important to start the ‘Honour Thy’ workshop tapping into the emotional connectivity participants have with their chosen personal image I asked them to bring along because it is a major component attached to, and regularly removed from, domestic archives.

Using the word ‘value’ while conversing about personal (family) archives can be quite contentious, but I would argue that without reminding people of and encouraging them to recognize the value inherent in these archives, we risk losing a vital part of our collective memory and heritage. Personal archives hold a wealth of information, emotions, and history that connect us to our past and shape our identities. By acknowledging their value, we are honouring them. Therefore, it is essential to engage in these conversations with sensitivity and a shared understanding of the importance these archives hold for both present and future generations.

Amouraé: Do you delve into the stories associated with the photographs in your archive, or are they long buried?

Cassia: It depends. As I pride myself on being a nosey person – always wanting to know and learn more – I am very keen with each photograph to unpack as much context. Unfortunately, some stories are long buried as people who once held that knowledge either forget or are too far out of reach to communicate with, have passed, or simply, they do not feel comfortable recounting. So, I refrain from asking more than once or at all, in some situations.

Amouraé: I remember you telling me that you’ve worked with a range of people, such as the homeless. How does this shape how you approach questions regarding memory, heritage, and inheritance?

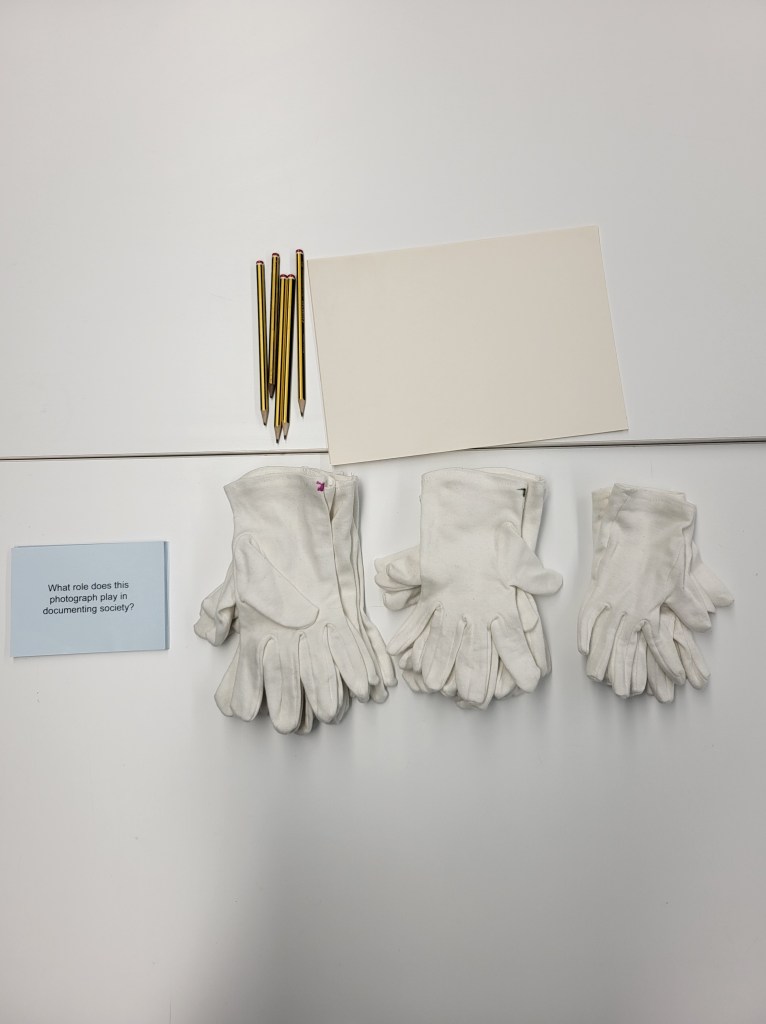

Cassia: Each workshop falls under the same umbrella of engaging with and teaching the community to preserve their printed personal photographs, both physically and contextually. The structure is typically split into three stages – discussion, creativity and conservation. As I am engaging with a range of different people, it is important to tailor the session’s delivery to their needs, lived experiences, and the space provided.

For example, I ran a session for Streetwise Opera – an opera company formed of people who have experienced homelessness to find support and empowerment as they work to rebuild their lives. To run a session for vulnerable and/or homeless adults, I needed to take into consideration that participants may not have access to personal photographs like other workshop attendees do. Participants were prompted to critically and creatively engage with my family’s photographs to explore the meaning behind family photography. Then using the same prompts, we unpacked three African-Caribbean composers’ personal photographs – Ignatius Sancho, Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, and Shirley Thompson. This session worked in alignment with Streetwise Opera’s plans to co-curate a festival with these workshop participants inspired by these composers of African and Caribbean heritage, looking more broadly at collective stories and migration.

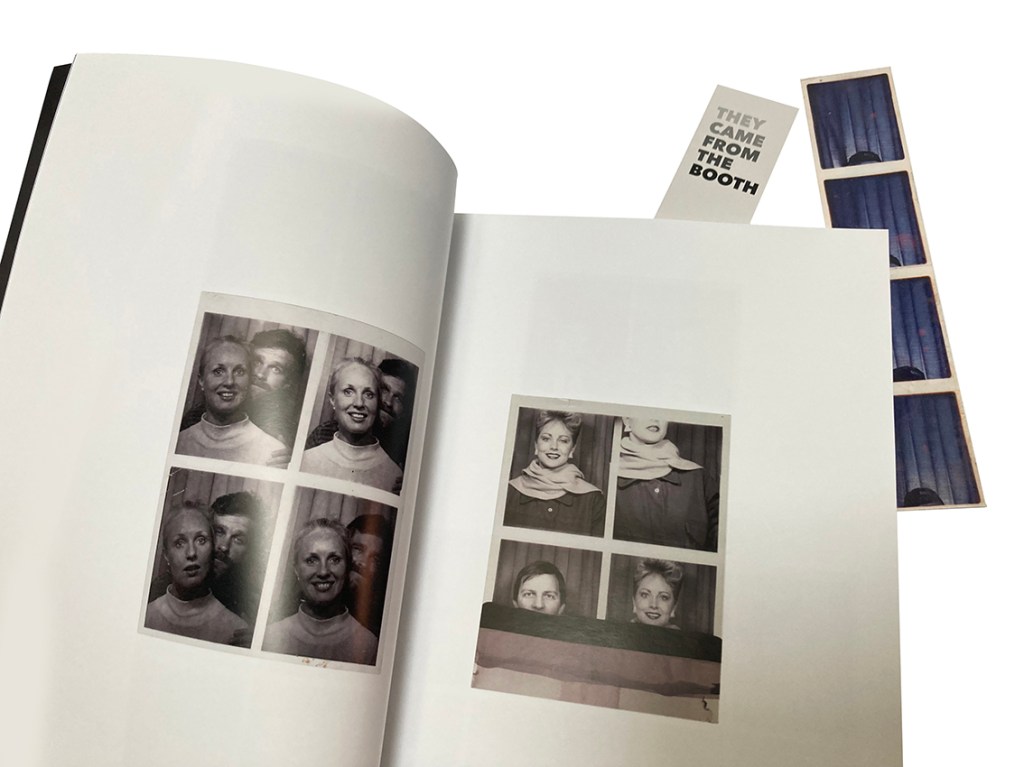

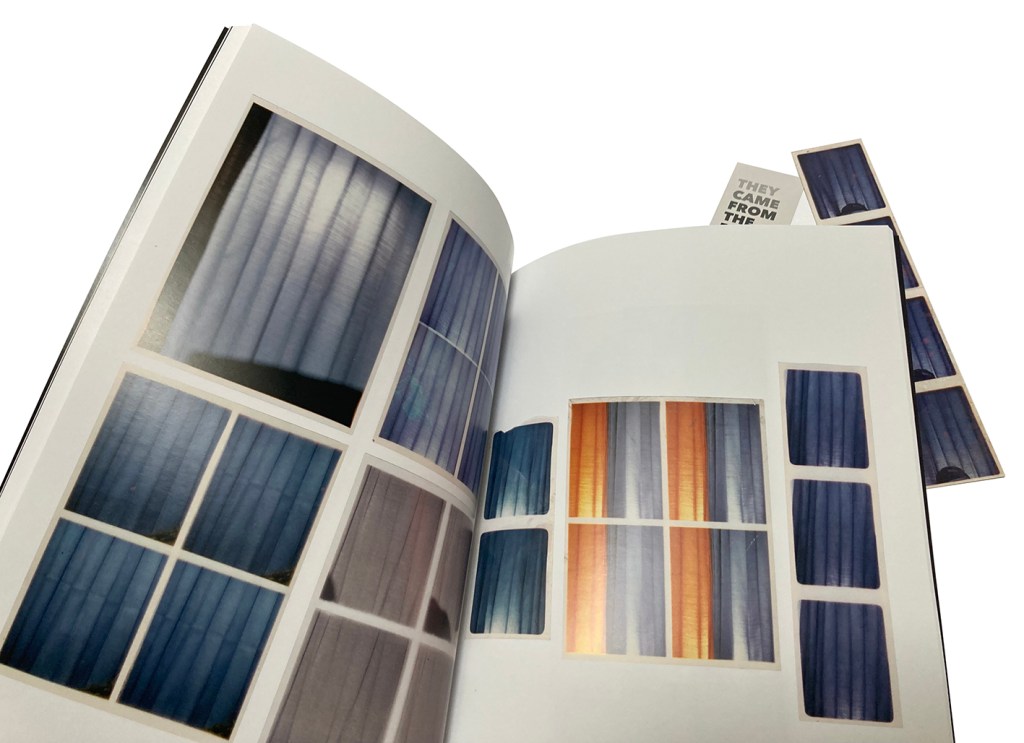

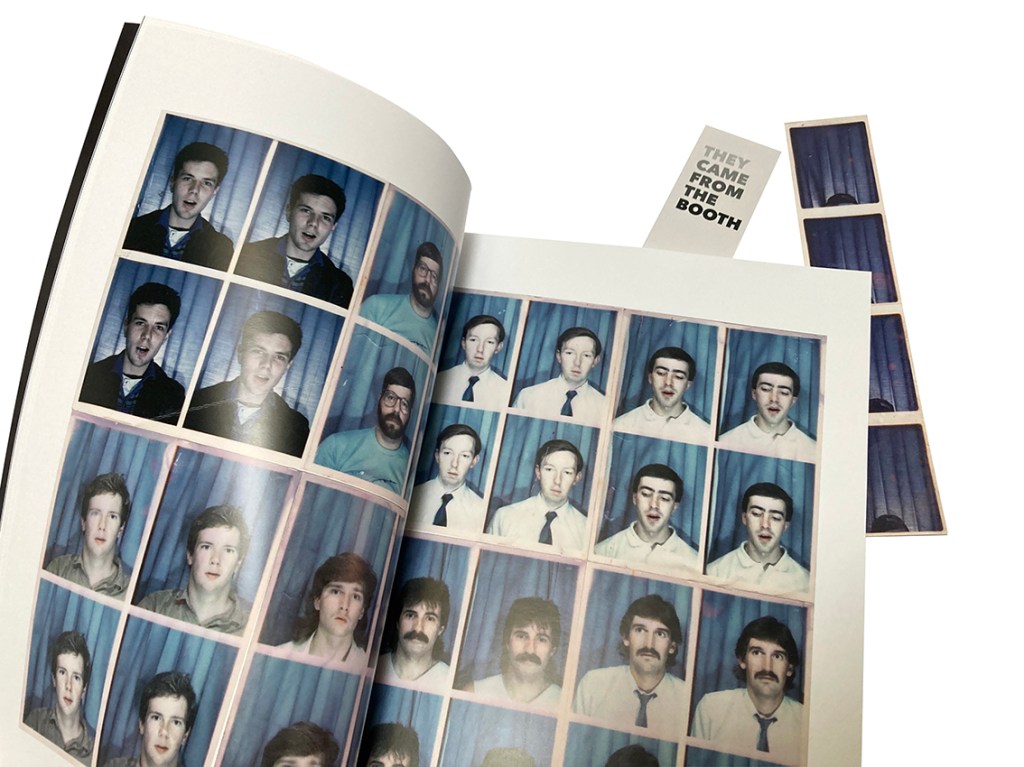

‘They Came from the Booth’

by Sue Smallwood

They Came from the Booth is a self-published book featuring over 200 found photobooth photographs collected during the early 1980s. The main set come from a single Photo-MeTM booth in London’s Kings Cross station, between 1987 and 1989. Designer Sue Smallwood tells us about her fascination with these images and the making of her book.

SS: The Photo-MeTM booth is one of the greatest joys of my teenage years. For a few pennies you could not only end up in tears of laughter – especially when caught mid-pose – but you could document your life: times had with best mates, school friends; the metamorphosis of my brother Nige and myself from awkward teenagers to monstrous hippies, punks and ensuing reprobates.

In the early 80s, unable to afford a coveted Polaroid camera (the only other way to create instant photographs), the Photo-MeTM booth was an essential resource for creating images for our band, The Trudy. We would each submit our ‘coolest’ photos to include in our D.I.Y. gig programmes. For me, this regularly entailed decorating the booth at London’s Farringdon station with different backdrops, or Christmas decorations, much to the bemusement of the ever-tolerant guard. The Trudy even wrote a song about a Photo-MeTM booth.

I had always picked up and kept discarded booth photos, but my modest haul was about to expand substantially when I moved to King’s Cross in 1987. To my delight, there was a row of Photo-MeTM booths in the station. Even more delightful was the realisation that one of the booths was on a go-slow. At the end of the day, there would always be two or three treats awaiting me in the ‘out’ tray – photos that had obviously taken far longer than the promised four minutes to process. The poser had left without them, either too impatient to wait or needing to catch their train.

An unashamed magpie and hoarder, I would take these discarded photostrips home and squirrel them away in a box alongside my initial collection. After a few weeks, I had amassed so many that I dug out a couple of old large photo albums from another of my squirrelly boxes and started to organise the photos. Fascinated by the minutiae of these stolen glimpses into other people’s lives, I spent many evenings contentedly deciding which of the photos ‘went together’, either visually or contextually. Those that seemed most jarring when set alongside each other provided me with the most satisfaction. The juxtaposition of particular images conjured up imaginary stories about the subjects’ intermingled lives and relationships. Some of the pairings felt quite poignant. Occasionally feeling the guilt of a voyeur, I nevertheless became somewhat obsessed with some of the people in the photos, even bestowing them titles such as ‘The Melting Lady’ and ‘The Ambassador and his Secretary’ – but I was never so presumptuous as to be on first-name terms with them.

Once the King’s Cross booth was mended, my collecting slowed, and the old photo albums that housed my treasures buried themselves further down in my hoardings. For decades. It was only in 2023, when I was approached about collaborating on an exhibition of ‘found’ objects (for my collection of Michael Clark/Leigh Bowery costumes – did I mention I was a hoarder?), that I commented I also had a collection of Photo-MeTM booth photographs. The albums were hauled out from their hiding place.

While the exhibition itself did not go ahead, I had already embarked on the design of a book showing all the photos (numbering over 200). As a graphic designer I am in my element with such a project. In 2017, I collated, transcribed and researched a collection of over 300 postcards from India, found in a carrier bag in my mum’s wardrobe. The cards had been sent from India from my great-grandfather, who had left his family behind in Kingston, Surrey, to chance his arm as an electrician in the days of the British Raj. He never returned. The resulting book, To Dear Harry Boy, encouraged me to focus more on book design, and the subject of collections.

As with my previous book designs, the Photo-MeTM book, They Came From The Booth, was created in InDesign, with image work carried out in Photoshop. Budget rather dictated the finish on this self-funded project, so I opted for digital print and a soft-bound, standard size (A4 portrait), with a matt laminated outer cover. The A4 format also accommodated the photos at actual size. The design was very straightforward and, for the most part, the spreads were laid out just as I had organised the photos in the original albums. With no particular deadline, I could just enjoy working on the book in my spare time, and re-acquaint myself with my old booth friends.

I mentioned the project to my old bandmate, Peter Tagg, to ask if he had the original lyrics of The Trudy’s song Photo Me (which was originally Peter’s idea, inspired by my photo collecting). He said the track had been recorded but never released, and that he had recently had it mixed and mastered; why didn’t we put out the song alongside the book?

So the first edition of books (150) also includes the CD of this track. I designed the disc using original photobooth photos of the band. The final spread of the book also celebrates the song, and the fact that the fun of the photobooth only added to this carefree era of our teenage lives.

My screen-printer friend Danny Flynn hand-screenprinted some bags for me, and together with a bookmark using the photostrip shown on the book cover, the package was complete. Another friend, Phillip Hawker of NoHAWKERS gallery in Brighton then offered to host a book launch (in November 2023), with an accompanying exhibition. It was a great celebration and wonderful to see people of all ages enjoying the images afresh – photos of these faces of strangers with whom I was now so familiar.

It was also fortuitous that the launch was in Brighton, as this led to me meeting Annebella Pollen, whose enthusiasm and generosity in introducing me to the wonderful world of mass photography/the popular image – and to people such as Eidolon’s Róza Tekla Szilágyi, Jen Grasso and Marco Ferrari of the Photobooth Technicians Project, and of course Nigel Martin Shepherd of The Family Museum – has opened up yet more opportunites to enjoy this fascinating medium.

With the passing of the years, photobooth photos come to represent relics from a time when people – either spontaneously or consciously – created images for fun, as a record of a moment to keep in a wallet, or to send to a loved one. Rushing through King’s Cross (you didn’t hang around there in those days unless you were up to no good), these people stopped for a moment and captured an image of a certain point in their lives – the booth providing a brief moment of sanctuary from the relentless frenzy of life outside.

My book is the story of just one Photo-MeTM booth. If walls could talk… But perhaps the photos say everything.

Sue Smallwood

Graphic Designer

@twinsglitterproductions

They Came From The Booth is available from sue@twinsglitter.com, £20 plus postage.

Q&A

Róza Tekla Szilágyi on the launch of Hungary’s Eidolon Centre for Everyday Photography

On 2 November 2023, The Family Museum will be speaking in Budapest at the conference ‘Talks on everyday imagery – the analogue and digital realm of the vernacular’. The event has been organised by the newly formed Eidolon Centre for Everyday Photography and will be hosted at Moholy-Nagy University of Design. The Eidolon Centre has been established in the Hungarian capital to research, study and showcase vernacular photography drawn from various sources. During the conference, international academics, curators and critics (Geoffrey Batchen, Lukas Birk, The Family Museum, Judit Gellér, Nathan Jurgenson, Sándor Kardos, Annebella Pollen, Joachim Schmid, Michal Simunek, Miklós Tamási and Joanna Zylinska) will come together to offer their views and approaches to this vital niche of visual culture.

Róza Tekla Szilágyi is Eidolon’s founding director. Formerly editor-in-chief of Artmagazin Online, she is also editor of the photobook Fortepan Masters, a selection of photographs in the Fortepan archive chosen by Hungarian photographer and photo editor Szabolcs Barakonyi. Founded in 2010 in Budapest, Fortepan is a community-led online photo archive comprising a large number of images depicting everyday life in Hungary.

In advance of the November conference, Róza interviewed The Family Museum for the Eidolon Journal about our thoughts on vernacular family photography and experience of running our project. We’re reversing the mic here to ask Róza about the origins of the Eidolon Centre for Everyday Photography and the aims for its development.

Róza Tekla Szilágyi, Director, Eidolon Centre for Everyday Photography. Photograph by Balázs Fromm

György Simó, Founder, Eidolon Centre for Everyday Photography. Photograph by Balázs Fromm

TFM: Helló Róza. Many congratulations on the launch of the Eidolon Centre for Everyday Photography. We are very much looking forward to joining you and the other speakers in November. Could you tell us a little about the genesis of the organisation.

RTS: Thank you very much – we are equally excited that you accepted our invitation. Eidolon’s genesis was in our work on the book Fortepan Masters, which took two years to complete. While working on it, our team had many opportunities to think about the importance and relevance of vernacular photography and the opportunities within the genre. Although Fortepan is not a wholly vernacular archive, because it includes images taken by professionals, it did make us realise how much we wanted to explore within the realm of ‘everyday photography’. Szabolcs Barakonyi’s concept for the book is that we usually set aside the content of these everyday photographs and use them solely for illustrative purposes based on their thematic or historical viewpoint.

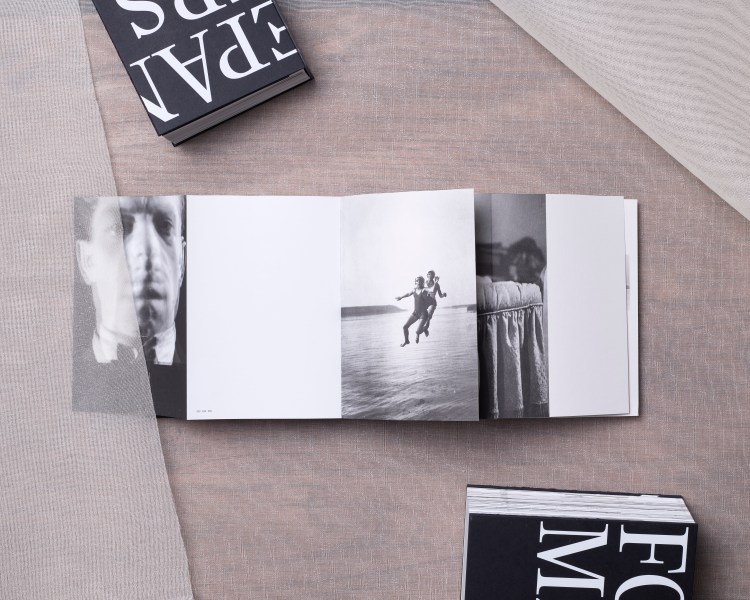

Fortepan Masters. Photograph by Csaba Villányi and Zalán Péter Salát

When the book was published and had some international success, we wanted to follow up on our ‘everyday photography’ ideas, and that is when the publisher of Fortepan Masters and a dear friend of mine, György Simó, made the decision that it was time to help formalise our ambition. His forward-looking decision to create the Eidolon Foundation enabled us to launch the Eidolon Centre for Everyday Photography. Moving forward, Eidolon will maintain Fortepan Masters’ approach of finding the artistic value, the ‘fine art’ hidden in the tsunami of vernacular photographs that exists, and we will also embark on a journey to explore contemporary, historical, aesthetic and scholarly thinking on everyday photography and its peripheries.

(For those who are interested, we still have copies of the English version of the second edition of Fortepan Masters available.)

TFM: What are your goals and hopes for this inaugural conference?

RTS: When we started developing the Eidolon Centre for Everyday Photography, we became aware that everyday photography – the ‘medium of the masses’ – is an interest shared by professional and amateur photographers, artists, researchers, academics and collectors. Hence there are many important initiatives, collections, groups, events and books centred around the subject. But it seemed to us there was no major institution dedicated to showcasing and publishing vernacular photography which could act as a centre for international discussion.

In 2023, our first year, I thought it was very important to put ourselves on the map, and what greater way to do this than to invite those whose thoughts and practice around everyday photography were inspiring us. This debut talks series in November is a chance for us to showcase what’s to come at the Eidolon Centre for Everyday Photography. We are interested in how our paper-based photographic heritage might slowly disappear if enthusiasts and institutions like ours do not invest in collecting and preserving it. However, we also want to focus on contemporary digital and social-media forms of vernacular photography. This first conference will be a crash course in the topic, touching on both old and new manifestations of the genre.

TFM: Hungary has a deep tradition of photography, with many Hungarian-born professional photographers – Brassaï, Robert Capa, André Kertész and László Moholy-Nagy, to name a few – breaking new ground in the medium in the 20th century. Would you say that, historically, vernacular photography has been afforded any special interest locally? For example, the Fortepan archive has been going strong since 2010.

RTS: The act of collecting and researching everyday photography has deep roots in Hungary. I do not want to exaggerate but, for me, it’s almost a kind of ‘Hungaricum’. One initiative that played a significant role in vernacular photography research in Hungary was the Privát Fotó és Film Kutatócsoport (Private Photo and Film Research Group, later Foundation), which grew out of a collaboration between András Bán and Péter Forgács. Their endeavour was to collect, research and exhibit both everyday photographs and films while establishing a research centre supporting visual culture research and education. For those who would like to know more, I highly recommend this article by Lucia Szemetová.

The Private Photo and Film Research Group was very much inspired by renowned cameraman Sándor Kardos’ vernacular photography collection, the Horus Archives. Parallel to his professional work, Kardos is involved with collecting amateur photography and his archive has been expanding for more than 50 years, becoming, in size, the largest private collection of its kind in Hungary. Comprising primarily amateur and family photos, the Horus Archives can be regarded as one of the first significant private vernacular photography archives, attracting international interest and featuring in European exhibitions, foreign publications and artistic interventions. At the Eidolon Centre, we have the unique opportunity to access this archive – we just opened the first of a new series of exhibitions showcasing previously unseen Horus Archives images. Moreover, we have created a website to showcase 1,000 photographs from the archive, and there are more to come!

Since the 1970s, initiatives like this have fuelled the interest of several generations of Hungarian artists who chose vernacular photography as material for their work. The Horus Archives was also an important precursor to Fortepan. Regarding Fortepan, it’s important to note that, as an ever expanding online vernacular photography archive, it holds a unique importance. Miklós Tamási, its co-founder, believes that the images in the Fortepan archive should be accessible to everyone, so all the photographs showcased on the site are published under a Creative Commons licence and are free to be used. Perhaps this democratic attitude, and the charisma of the founder, are the reasons behind the unbelievable popularity of Fortepan.

TFM: The name of your Centre is inspired by Roland Barthes’ use of the word ‘eidolon’ in his book Camera Lucida, in which he contemplates the nature of photography and what is “emitted” by the subject of an image. How do you think the discourse around vernacular photography and its impact on us as viewers is evolving today?

Vernacular photography is a widespread but strangely under-represented genre in the context of the history of photographic imagery, despite the fact that it represents the larger part of our visual heritage of the last 200 years. It lies on the border of creativity and the everyday, the mundane and the unrepeatable, art and history. These images play a crucial role in documenting our history because they represent a collective memory. The vast majority of photographs of ordinary people, showing their lives and the details of everyday human existence, taken by other ordinary people, are bound to disappear. Even if we think about the daily practice of smart-phone photography, most of these images are never looked at again. A quantity of paper vernacular images are held by museums, but we have reason to believe that without investing in their preservation, an invaluable part of humanity’s history and our visual culture could disappear.

I do think that the growing interest in everyday photography can teach us something about ourselves. Buying film cameras seems to be a nostalgia-fuelled trend at the moment, but I also advise everyone to look at their family albums once again, because they are worth looking at. And not just in the way that we quickly swipe through digital photographs nowadays.

TFM: What next for the Eidolon Centre for Everyday Photography?

RTS: After the conference, we will create video and written materials based on our speakers’ presentations, so those who could not attend the event will be able to join the discussion. Besides continuing our work with the Horus Archives, we have an online magazine, the Eidolon Journal, and we are very eager to keep creating engaging content, articles and interviews – so check in weekly!

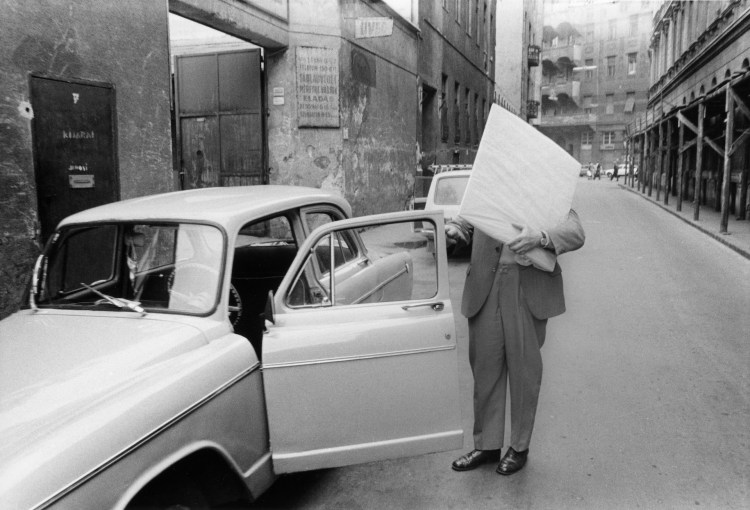

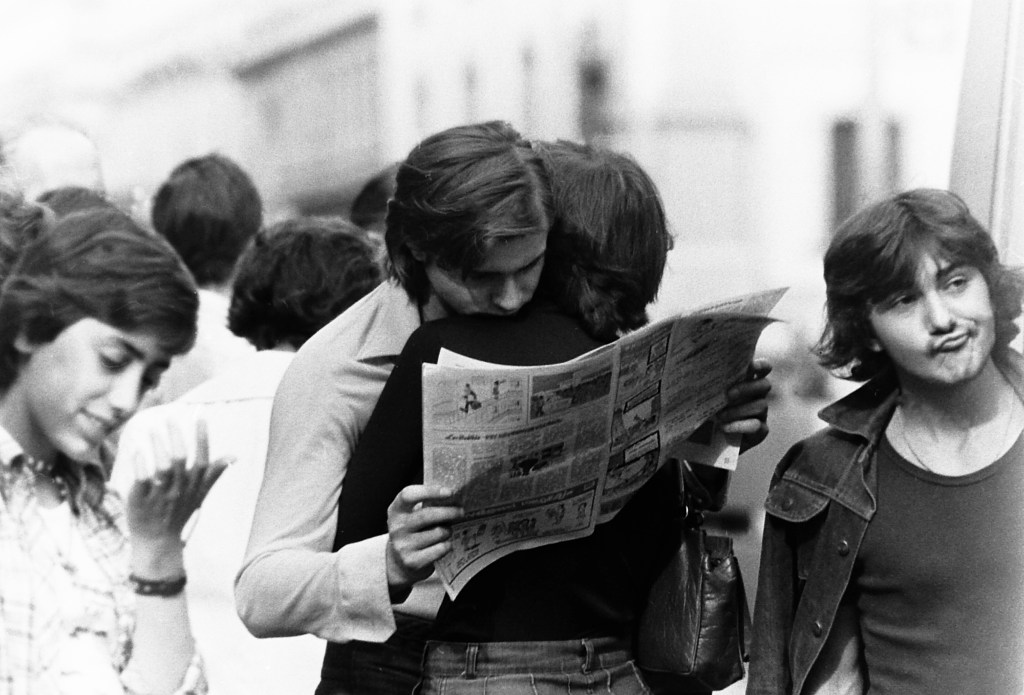

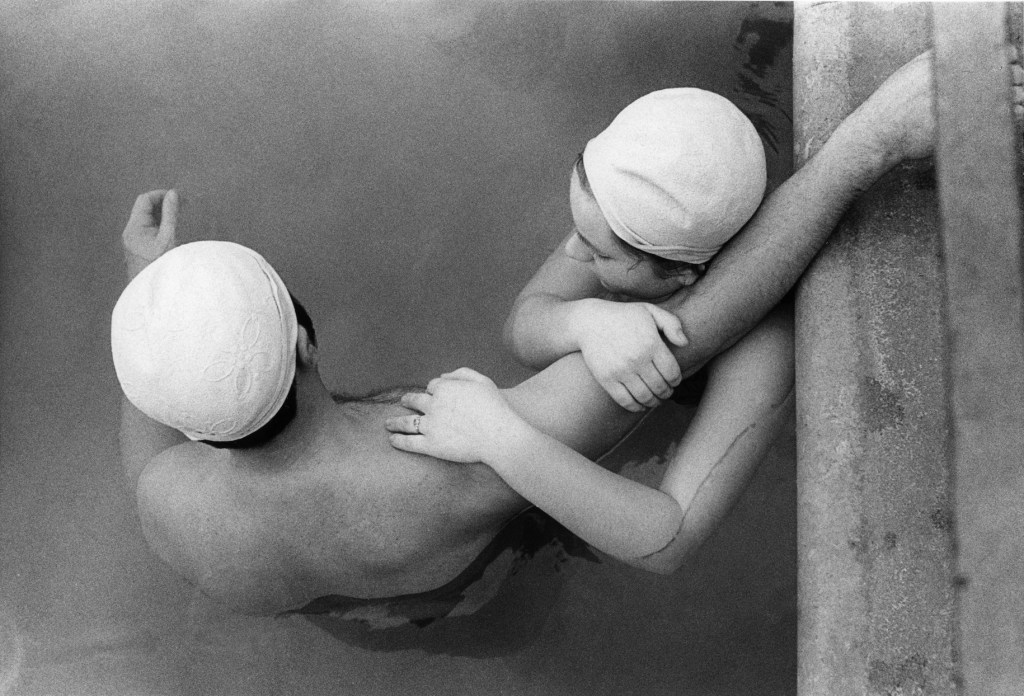

In December 2023, we are opening the first exhibition of works by Sándor Kereki (all images above). Kereki was born in 1952 and at the age of 16, while still in high school, started taking pictures with a camera that his father gave him for his birthday. He never studied photography in a formal setting. Some of his pictures were uploaded to Fortepan two years ago, but his photographs deserve to occupy a larger space in the canon of Hungarian photography. Therefore we want to organise an exhibition that draws on Kereki’s entire oeuvre – it’s a project that we are very much enjoying.

Looking ahead to 2024, we are developing an exhibition project that will hopefully let us tap into uncollected everyday photography material in Budapest. We are also planning to engage in international collaborations, and will certainly organise a second conference next year.

Interview by Rachael Moloney

Marcela Paniak on her work as an archivist and project exploring her own identity through family photography

We’ve met many inspiring people at our weekly stall at Spitafields market, including Marcela Paniak, on a visit to London from her home in Poland. Marcela has worked as an archivist at the National Film Archive – Audiovisual Institute in Warsaw and specialises in digital archiving. She is completing a doctoral project at Łódź Film School, with whom she also collaborates on various photographic projects.

Her professional mission is to popularise ways of working with various types of archives, from domestic ones created by families to community and public examples.

TFM: Cześć Marcela! It was a pleasure to meet you in London. Could you tell us a little more about what you’re working on at the moment?

MP: I am still working on my doctoral project, which is about my own identity and the identity of family photography. Just as family photography is not a refined entity, neither is my own self-knowledge. In my doctorate, I treat family photography as the subject of my research, and also as a medium and a means of expression.

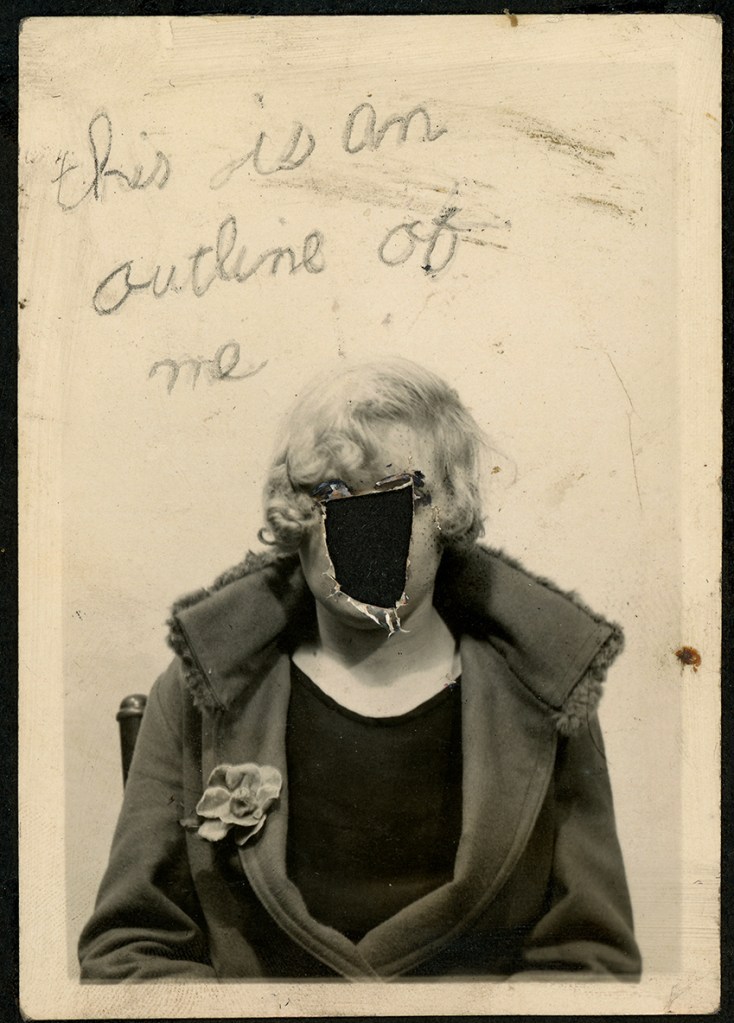

To investigate why family photography is such a marginalised genre of photography, I produce different series of photographs using both historic and modern methods. Reconstructing various processes, I pay special attention to some commonly used methods of altering a self-image. All the changes I make to a picture are so intensified that the perplexity about the boundary between the truth and falsity of the representation becomes more and more apparent. The self-portraits become more and more unrecognisable to others, and this is what helps me to discover my own identity.

My images present me in different roles – as a parent, as a young woman, as an elderly man, as a grandmother and as a grandfather or a child. I am in front of and behind the camera, and also a viewer of my own photographs, which are very similar to thousands of other family photos. In this way, I comment on common trends in family photography and also on my own identity. I believe that my doctoral project is universal and personal at the same time.

TFM: To date, vernacular family photography has not been the subject of widespread academic study. What first sparked your interest in the subject?

MP: A natural heart reflex. As I feel a connection between family photography and my own identity, family photography has become more and more significant to me, not only in my photographic work, but in everything I do in life.

My photographic studies at the Film School in Łódź have been focused on self-image, identity, history and memory, and images themselves. Vernacular family photography has not been a specific subject of study. I first used this term during my doctoral studies when I realised that Warsaw is the location of many photography centres that promote personal photographs of universal value. In that moment, I knew this was the right direction – to concentrate on family photography, which is not perhaps popular in official studies but is very common in ordinary life. These images have such value for one’s heart.

TFM: We agree with you that family photographs tell incredible stories about individuals, but also about society and specific moments in history. You are very interested in what emotions family photographs evoke in us when we view them, and how we construct memories by looking at family photographs. Could you expand on these thoughts and what reactions you think family imagery provokes.

MP: Family photographs are intensely related to our emotions. The emotions are just as present when you decide to take a picture of a situation as when you view the photo and that captured fragment of your life later on. The emotions that arise when taking and viewing photographs of a family are related to the specific nature of photography itself.

Photography has always had a special dual character. Due to the mechanics of the camera, it is a specific documentation of reality, but at the same time the creativity of the user makes for a more or less representative image of the world. So it’s the perfect way to perpetuate the most emotional moments in one’s family’s life.

When meeting other people to talk about their family photos, I noticed another important characteristic of this particular genre of photography. Each photograph had countless stories told about it by different people, who each remember a specific event in a completely different way. This made me conclude that despite the permanency of photography, human memory is inconsistent – it changes with how people change in their different states in life. What one remembers is decided by one’s current emotional state. That is why one photograph can provoke so many different emotions, each with its own value.

I often wonder how we would talk about the same memories without the presence of photography? Many family memories only exist because of a picture. But also, many memories can be replaced by an image and never be recalled. It is so powerful how memory works with our sense of sight – the sense so entwined with photography.

TFM: You’ve spoken about the importance of creating a “community culture” around the “social memory” we experience when creating and looking at family photography. Could you explain why you see this as vital? You also run a series of Photography Meetings in Warsaw, where you invite people to come and discuss family photographs and how to create archives. Who comes to these gatherings and what kind of topics do you discuss?

MP: We all have some experience of family photography. All the habits surrounding it constitute a very individual experience confined to the home circle. When the environment of these private rituals becomes public, there is an opportunity to pay attention to different aspects of family photography, the less intuitive aspects. We try to concentrate on these aspects during our photography meetings.

The people at our meetings are very diverse – mainly adults, young and old, but also children – so there is a chance to continue the family history from one generation to another. In addition, these meetings are intended to show each person that individual stories are just as important as official records of history. For some time, these personal stories have been in the background. It is crucial to me to point out that every single human story is as valuable as any universal national history. An individual’s point of view is the most precious for me because of its unique emotionalism.

In our meetings, we also discuss useful tips, such as how to take care of family archives at home; how to organise a collection; how to digitise materials; how to promote archives that are in public circulation. These skills are very important for family photography in today’s highly dynamic world.

TFM: As amateur photography habits have transitioned from analogue to digital, what is the role of archiving today in your opinion, and projects like yours and ours?

MP: We are at a special moment in that we are able to experience both analogue and digital technology; the potential and the menaces of both material and non-material photography.

On the one hand, the traditional paper family album has become something that tempts us, because it is different to contemporary digital photography. And technological advancements mean we can now preserve printed photographs and share them widely, on the Internet, for example.

On the other hand, the numerous digital family photos that we think are being preserved in our computers, will constitute, from a future point of view, an ‘archival emptiness’. Technical devices and their operating systems change very rapidly now. Perhaps the contemporary family photograph will not even survive its creator’s own lifetime.

The transition from analogue to digital has therefore positives and negatives for the genre of family photography. That is why archiving both – historic and contemporary photographs – a conscious caring for them, is so important today. Currently there are a lot of archival projects, but it is worth paying attention to their potential uses, so that they do not become solely storehouses of our history.

TFM: Over the past few years, we’ve seen more and more artists using vernacular family photography in their practice. Do you think this trend can change our understanding of family photography and why it is such a powerful form of image-making?

MP: Family photography and family photography archives are becoming very popular resources nowadays. This has resulted in a change of status for family photography – not only because its configuration is now different but because of the omnipresence of images in general. I think this is one reason artists are following this trend.

A family photograph is both an image of something very emotional and a very emotional experience in itself, even though the object of the image may be far removed from the present reality. By looking at an immortalised moment of a place or people we feel like we were there with them. It is something magical in a way.

What is more, because family photography is about various individual human stories, the chance to communicate something fascinating to others is endless. So this genre is a never-ending source of inspiration – for artists and for everyone, including me.

TFM: In your work, you ‘stage’ your own family photographs to convey certain ideas about image-making and identity. Could you tell us why you are interested in this approach?

MP: OK, now I will share my secret with you – my name is not my family name. I chose it. For more than a decade, I have been using the signature ‘Marcela Paniak’ to signify that I don’t really know who ‘me’ is. All this time, I have been getting to know myself.

To do so, it was natural for me to use family photography as it is one of the ‘unknown’ genres of the medium. What is more, as I prove in my doctoral project, in family photography it is normal to ‘stage’ yourself to present your image in a certain way. The practice of self-presentation in diverse and various ways helps me to get to know myself. By changing my self-image so intensively, I’m getting to the point where I finally feel myself. It is crucial to return to a feeling of being natural, no matter who you feel you are and how you are labelled in your social life.

Just like in family photography, beyond everything I may try to describe in words, an image has something inexplicably magical about it that really fascinates me, even if there is no precise name for what that is.

Interview by Rachael Moloney

Goa Familia on the origins of their project and future ambitions

Among the growing number of archival projects centred on vernacular family photography, Goa Familia has always caught our eye. Launched in 2019, it was borne out of the multi-disciplinary Serendipity Arts Festival, which is anchored in the South Asian region and active in initiating various arts programmes.

Curator Lina Vincent and creative collaborator Akshay Mahajan were sought out to develop the Goa Familia project as a means of exploring family histories and community narratives across the Indian state of Goa. Through a series of open calls for people to share their family photographs and albums, as well as oral histories and other forms of ancestral memorabilia, Lina and Akshay have uncovered many wonderful and illuminating stories and anecdotes about the lives of several generations of Goans, and they continue to build the project the project around this material. We were delighted to talk to them both – London to the Goan capital, Panaji – about the journey they have been on so far.

TFM: Hello Lina and Akshay. It’s a pleasure to be in touch. Could you tell us how Goa Familia began.

LV: The project was conceived jointly by Rahaab Allana, of the Alkazi Foundation for the Arts, and Serendipity Arts Foundation, headed by Smriti Rajgarhia, who has been deeply involved with archival documentation. Early in 2019, Rahaab and Smriti were looking for contacts in Goa with an interest in community engagement and archival research. Owing to our respective backgrounds in photography and art history, they reached out to Akshay and I, and we became Team Goa Familia. We had complete freedom to plan the framework, set the context and develop a methodology that suited us to execute the project. We began by simply pooling our local knowledge, contacts and resources to locate and connect with those in the community who may want to contribute.

As a curator, and someone working with physical objects and largely published histories, to engage with oral histories and the amorphous quality of human memory was an exciting prospect. It has also been a learning experience to engage more deeply with the history of photography in India and the diverse socio-cultural dimensions it has and generates.

AM: What attracted me to the project was the act of putting together such an archive and the possibilities that give birth to many readings of it. Unlike in the West, where larger visual public archives exist, in Goa, and by extension India, these photographs are held in non-traditional archives – in family homes and photo albums. The idea of looking into these archives was interesting, to say the least, especially to view Goa’s historicity.

Our first milestone for Goa Familia was to launch a “work-in-progress exhibition” at the Serendipity Arts Festival 2019, to showcase the project.

TFM: You describe Goa Familia as an “evolving archive”. Have the connections you’ve made with locals and the stories you have uncovered met your expectations about the family photography that exists in Goa, and what it means to your contributors?

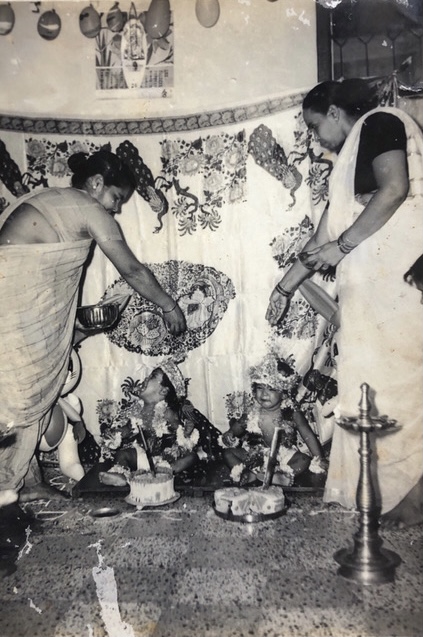

LV: We began with an open slate and two main objectives – to interview families and access albums from as diverse a population of Goans as possible; and, in a connected vein, to break the composite stereotypes that have been built around the representation of Goa and Goans in popular media. While a prominent part of the region’s population is Catholic, there is also a sizeable demographic of Hindus and, to a lesser extent, Muslims. We uncovered the names of a number of photography studios across Goa, founded by Catholics and Hindus, which were popular with local communities.

It was the upper class who could afford to use these studios as well as buy personal cameras for their own use. We traced a distinct pattern among families, of recording celebrations like weddings, festival gatherings and even funerals. We have also been able to view some albums belonging to the Goan diaspora and have unearthed some incredible stories that cross continents.

It was a slow process in the beginning. It helped a lot to have personal introductions to families who then opened their doors and their archives to us, and later facilitated a greater outreach for Goa Familia among their networks. The material and stories we have gathered, and our experiences with each family, have gone beyond our expectations. However, we have also come across several disappointing instances of albums being misplaced, lost, burnt or washed away in accidents, or eaten by insects.

AM: One of the ideas behind Goa Familia was to foster a community approach to the archive. We hoped to bring the many protagonists required in building such an archive into one room – mainly the photographer and the photographed, the camera and the spectator – and to witness the resulting encounter. The 2019 exhibition in Panaji was a place where, for a brief moment, the oral histories traversed into the realm of art just by putting them side by side with the physical photographs. We saw how these old photos coupled with the oral histories about them dredged up family memories for some visitors. Others uncovered serendipitous connections to the sometimes long-dead subjects of the photographs. Each of these encounters was a big learning curve for us, as they showed that images are not static when you gather all the protagonists in a room and thereby build an archive.

Since Goans are spread all over the world, we wanted to see if we could find stories from the large Goan diaspora. As an example, I was able to connect with Joyce D’Silva, who is now living in Liss, Hampshire. Joyce is the widow of Amancio D’Silva – a pioneering Goan jazz musician and genuine expressive genius who spent most of his musical career in London’s open-eared jazz scene in the 1960s and 70s. Among other things, Amancio was one of the early evangelists of fusion music.

My favourite moment was talking to Joyce when she was recalling the first time she met her future husband. A young, Irish teacher, she had barely been in India two weeks when she walked into Davico’s Restaurant in Shimla, in the summer of 1964. “We walked into the restaurant and there was a quartet playing with this handsome guitarist in the front,” she said. “I took one look at him and I thought to myself, ‘That’s the one!’” Even though Amancio never achieved the kind of recognition that he deserved in his own lifetime (and most Goans still don’t know that the likes of Amancio D’Silva fearlessly broke down barriers and traditions with his searing brilliance), more importantly he found success in every other way – as a husband, a father and a human being.

TFM: Have there been any surprises that stand out for you? In one of your Instagram posts, you talked about a “strange interconnectivity to archival photographs”. Could you elaborate on this thought.

LV: Yes, the underlying connections have been intriguing and exciting. For instance, we interviewed the children and other relatives of a well-known musician, Pandit Prabhakar Chary. We gathered images of Pandit teaching a number of students the tabla. Later, on interviewing the Bharne family, owners of a prominent business establishment in Panjim town, we found among their photographs images of the young sons of the house posing with Pandit Chary, who had been their guru. It turned out that some of the photographs of the Bharne family were taken at the legendary Lisbon Studio, the current proprietor of which we had interviewed. We also found links between families through memories they narrated of having been neighbours in far-off Kenya, or having been introduced by the same village matchmaker!

AM: During our various interviews, we have found this “strange interconnectivity to archival photographs” exists in relation to photo studios especially, whose relevance is now diminished. At first we chalked up these connections to coincidence, and to the nature of family bonds in Goa, in relation to people’s use of the studio. Until relatively recently, most Goans did not own their own camera and photography was strictly a studio affair. There was a time when families would throng to them. They would travel to studios in the cities and nearby market towns, dressed in all their finery to strike quiet poses to mark weddings, christenings and occasions big and small. Like in many places in the post-colonial world, these studios became centres of photographic culture in a way. It was therefore only natural to see old studio stamps repeated in many a family album.

TFM: Based on your experience of the project, how would you describe the relationship people of different generations have with analogue photographs and albums in Goa, or India at large? Here in the UK and in the US, we’re aware of the increasing number of family albums and photographs that now end up on the open market, where they are snapped up by collectors and artists. Major museums are also paying more attention to vernacular photography. Are these trends in India too?

LV: In India as well there has been a surge of interest in archival photography, as well as art projects that revolve around it as a form of history-making, documentation and expression. This can be seen in tandem with a general investigation of identity and ancestry, connected at a mundane level with the potentialities of digital scanning (through phones and other accessible technologies), which allow people to ‘share’ and ‘post’ on social media.

The experience of fragmentation has become an inescapable part of the contemporary world we live in: migration, dislocation and loss of roots have divided entire communities, and are changing the way living generations perceive their pasts and look toward the future. Many have come to realise the preciousness of retaining memories, and of conserving the notion of belonging, in whatever form that may be. Reviving visual histories also has a complex relationship with responses to political agendas and government policies that question nationality, religion and patriotism.

AM: Family albums tend to show constructed, idealised families, marking mostly happy occasions such as births, weddings and holidays. It was interesting to record the oral re-telling of the albums that we came across – the reading of photographs both individually and together when they are placed in an album. We received responses that touched on personal memories, but also on larger stories of Goan history, of the Goan experience, of migration.

We found that there was usually a ‘memory keeper’, who kept all the photographs and memorabilia in a family. This memory keeper was almost always a woman. It was important to record these interviews to see how the meanings of the photographs change in their telling; for example, touching the physical photograph and, in the act of remembering, a daughter saying, “My father was a gentle man”. We also met people who didn’t like looking at old photographs and preferred to live in the moment – the pictures were too hard to look at.

There is definitely a trend of collectors and museums acquiring larger archives, especially of 19th century photography, in India. Although, with the exception of hand-coloured photographs, I haven’t seen much movement around this with 20th century photography here. There haven’t been any large-scale artist projects using found photography, such as the Beijing Silvermine project in China, for example. However, there are several artists in India interpreting their own family archives, like Sukanya Ghosh, who reworks her family pictures to make collages, sometimes sculptural ones. It’s only a matter of time before people start collecting more vernacular photography here.

TFM: What are your future plans for communicating the stories you’ve come across, and for involving local communities in the project? We saw that in November 2020 you featured some of the oral histories you have gathered so far @serendipityartsfestival

LV: We have worked on a dedicated website for Goa Familia, which will keep expanding as we upload the archives that are digitised. The digitised versions are shared back with the families for their records. We are offering advice and basic dos and don’t’s for families who want help conserving their archives. We mean to make our Instagram and Facebook pages as interactive as possible by inviting shares, posts and tags, even from those who may not want to contribute to the Goa Familia digital repository in a formal way.

The project is also about generating awareness and interest in photographic histories and making sure that these aspects of our past are carried forward for posterity. All being well, this year [2021] we hope to have another physical exhibition with objects and memorabilia loaned from contributors and to create public interactions for sharing personal and collective stories.

I think both Akshay and I (and our young research associates) would like Goa Familia to be a long-term project with different trajectories, which finds form in diverse media such as books, public art projects, exhibitions and other programmes. The project has certainly changed the way I perceive Goa and her people.

AM: We have had to adapt our methods since our initial approach was oriented to field research. Firstly, since we had a lot of leftover material from 2019, we wanted to expand on some of the stories and share the full archive of digitised photographs on our website. Nishant Saldanha and Manashri Pai Dukle, two of our associates, are working with their own family archives. We thought it would be a perfect opportunity for them to conduct an in-depth telling of their own family histories in their own voice. The resulting archives are deeply personal. Nishant’s piece is a moving tribute to his grandmother, Ada, and her idyllic childhood growing up in Dharwar, a township in Goa’s neighbouring state of Karnataka. It was here that her father, the famous poet and writer Armando Menezes, was principal of Karnataka College, while living exile from his native land.

Our hope for the future is to grow the archive, keeping community engagement at the heart of it. We are also hoping to put together some resources in Goa for archival restoration and preservation.

Interview by Rachael Moloney

Hackney Archives on their RA Gibson Collection

In The Family Museum archive we have a small white wedding album, with the embossed title ‘Gloria & Eddie, 12th June, 1960’. We came across it recently in a Brick Lane flea market in East London. What drew us to the album were the radiant images inside showing a Jewish couple and their families celebrating a marriage at Shacklewell Lane synagogue.

Beautifully composed, the photographs were taken by studio photographer Ronald Gibson, whose ‘RA Gibson’ business card is tucked inside the back of the album. We soon discovered that Gibson had played an important role in documenting the people of Hackney over four decades. A chance meeting at another London flea market led us to Hackney Archives, who coincidently have an ongoing project focused on a large number of Gibson’s images and the community he photographed dedicatedly for more than 30 years.

We asked Hackney Archives to tell us more about their acquisition of Gibson’s photographs and the work they’ve been doing around the collection. A selection of the images they’ve digitised to date is currently viewable on Flickr.

TFM: Hello Hackney Archives. We were intrigued by our found wedding album as it was such a joyful local East London story documented by a photographer with a real talent for capturing his subjects. The images all have an extremely warm-hearted quality. How did you first come across the work of Ronald Gibson?

HA: We acquired a large number of Gibson’s studio portraits and event images from photography enthusiast Kevin Danks, who donated 144,000 negative captures – in 40,000 strips, totalling six miles of film – to us in 2014. Kevin had bought the negatives on Ebay. After studying them, he felt the photographs represented such an important slice of social history within Hackney that they needed to be held in a public archive and seen by as wide an audience as possible. Thanks to a grant from the Esmée Fairbairn Collections Fund we’ve been able to archive and digitise the photographs.

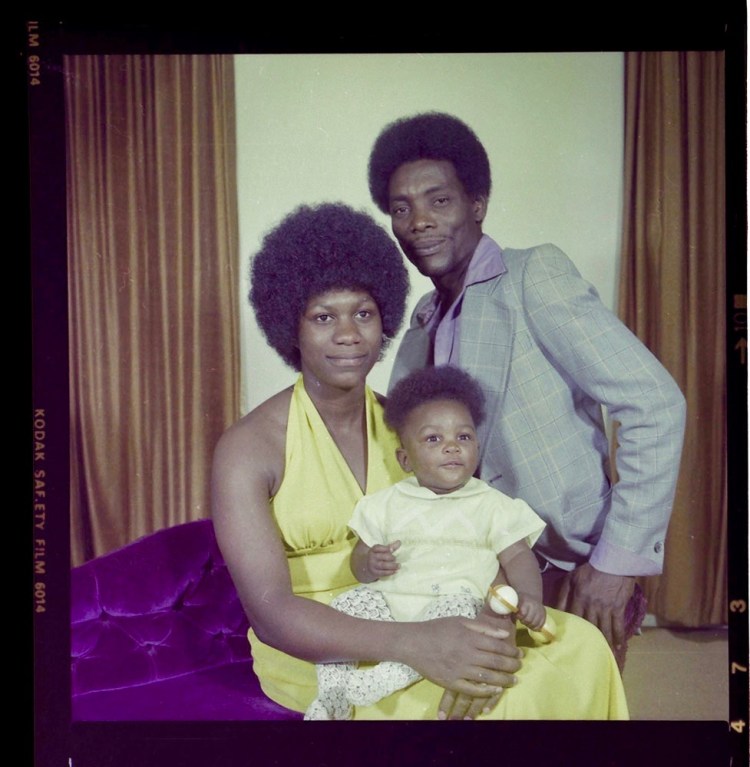

TFM: The collection you now have includes wonderful studio portraits and family event photographs taken from around 1952 to 1978. They give a vivid visual account of the lives of local people who wanted to mark their educational achievements and professions, their families and personal style. How have you approached communicating the collection to Hackney residents today, some of whom may be connected to the subjects shown in the images?

HA: Between 2014 and 2020, Hackney Museum has put on three exhibitions featuring Gibson’s images. The themes for our shows have ranged from African and Caribbean fashion to the life stories of the subjects, who reflect East London’s growing migrant communities from the mid-20th century onwards. The social and historical aspect of these photographs is what struck Kevin Danks deeply. When we put on our first ‘RA Gibson’ show, Strike A Pose: Portraits from a Hackney Photo Studio, in 2014, Kevin commented: “The collection illustrates social change in Hackney after the Second World War. In the 1950s almost every shot features white, working class people and by the early 1970s this changes and the diversity we see today is evident.”

In 2018, as part of the Museum’s show Changing Faces, Hidden Stories, we held community sessions to try to identify some of the subjects in the thousands of images we have, and to discover what RA Gibson portraits local people may still have in their possession. We organised ‘Reminiscence’ sessions with local church groups and lunch clubs, and publicised the collection on social media. Any comments people made about the photographs will be added to the catalogue entries for the respective photos.

The digitisation of the images and our engagement with the local community about the photos are ongoing projects for us. We’re keen to keep interacting with the public as much as possible and to gather more information about the people who were photographed.

TFM: RA Gibson was clearly a very popular photographer among the Hackney community. How much do you know about him?

HA: Gibson was self-taught and first opened a studio in Mare Street, Hackney. Around 1952, he relocated to Lower Clapton Road, where he remained in business until 1989, when he sold the studio to new owners. For the growing African, Caribbean and Asian communities in the borough, Gibson’s was the go-to studio for portraits which people could send home to their families, showing their lives and progress in the UK. In the 1960s and 1970s, these photographs reveal local people taking great pride in their new families and accomplishments here in the UK, and their individual identities, expressed through their fashion, for example. By first-hand accounts, Ronald was very well liked by the people who came to his studio and he built genuine and long-lasting relationships with his customers.

TFM: Warmth and trust are evident in these portraits and clearly kept locals coming back to create what were prized possessions for many. We’re thrilled we came across Gloria and Eddie’s album and it led us to you and this brilliant collection. Thanks for chatting with us. If anyone reading this has a connection to any of the images, or has RA Gibson photographs they would like to share, how should they contact you?

HA: We would love to hear from them. Please email us at Archives@hackney.gov.uk or call + 44 (0)20 8356 8925.

Interview by Rachael Moloney

Artist and curator Barbara Levine on the major acquisition of her photography collection

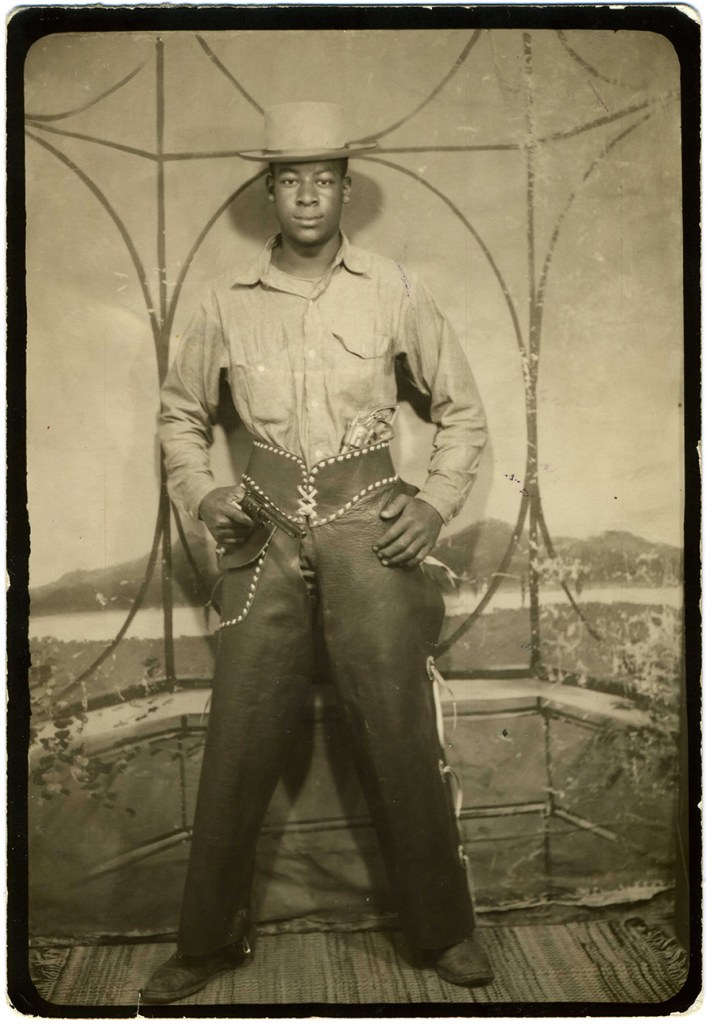

In June, we learned the exciting news that the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston (MFAH) has acquired the Barbara Levine and Paige Ramey Collection, an extensive archive of vernacular photographs and photographic objects built and curated by Barbara and Paige over the past 30 years. The images are focused around distinct themes, including African-American studio portraits, LGBTQ life, Mexico and the border, gun culture, sideshow stars and superheroes, “women only”, and altered and manipulated photos, Among the many unique photographic objects in the collection are examples of ‘Fotoescultura’ (photo-sculpture), ID badges, photo puzzles, hand-beaded portraits of bullfighters and funeral announcements adorned with tintypes.

Barbara and Paige are based in San Miguel de Allende, Mexico, and Houston, Texas. Barbara was bitten by the collecting bug as a child and has been dedicated to preserving and sharing vernacular photographs ever since. She was a contributor to the launch edition of our Famzine, and since meeting (albeit virtually), we’ve been hugely inspired by Barbara’s dedication to curating found images and the way in which she gives this photography new life in her practice.

In her own words, Barbara is an “artist who collects vintage photographs”, using the images she finds as a jumping off point for both artistic and curatorial projects. Her photo collages have been exhibited and published widely and were acknowledged with a LensCulture Artists Award in 2017. Barbara is also the author of several highly recommended books on vernacular photography, including Snapshot Chronicles: Inventing the American Photo Album (2006), Around The World: The Grand Tour in Photo Albums (2007) and People Kissing: A Century of Photographs (2019), all published by Princeton Architectural Press.

Paige has extensive experience running arts organisations and in the preservation of pre-digital and time-based media. Her early career was in dance and video art in New York City, where she worked as a performer and videographer with seminal artists such as Elizabeth Streb and Yvonne Rainer. Since 2014, Paige has been consulting and co-curating for Cherryhurst House, a visiting artist and exhibition space in Houston.

Barbara and Paige share all their projects on their website projectb.com and images from their collection on Instagram at projectbphotos.

We caught up with Barbara over the wire, London to San Miguel de Allende, to talk about the MFAH acquisition and the photographs and objects she and Paige have lovingly curated over three decades.

TFM: Hi Barbara. Huge congratulations to you and Paige on this news. What does this acquisition mean to you both as long-term collectors of vernacular photography?

BL: Thank you! For us, it is the next step in the life of the collection, revealing more of the stories and ideas embedded within the pictures and how they fit within the larger history of photography. With the MFAH curators, we are involved in a wonderful dialogue about integrating the collection into the museum’s photography and overall collection, and how best we can encourage the study of the material. For example, a museum fellowship will be offered, inviting collaborative applications from an artist (not limited to photographers) and a scholar (historian, art historian, writer, etc).

Overall, these efforts and shared sensibilities enhance our relationship with the photographs and photographic objects, and inspire us to want to do more. For me, the collection has always been intertwined with making art and a spark for curatorial ideas. Paige and I will continue to have access to the photographs and will work on future projects such as books, exhibitions and collaborative artworks.

TFM: Arguably, ‘vernacular photography’ is an increasingly wide term to describe the niches of amateur and found photography. You and Paige prefer to call your collection ‘PhotoMania’. Could you explain why?

BL: Vernacular is an off-putting and confusing term for many people and typically requires explanation – a contrast to the material itself, which is easy to relate to and often humble in origin. We started calling the collection ‘PhotoMania’ to convey the joy viewers find in the material and the passion and fascination with which we have built the collection. This archive celebrates our collective enthusiasm for a medium that is part of nearly everyone’s life and experience.

TFM: Other major museums and galleries around the world have acquired relatively small amounts of amateur and vernacular photography to date, and certainly, as far as we are aware, nothing that compares to your collection. Do you think more will do so in future, given the growing number of found photography projects out there now, especially on platforms like Instagram?

BL: It’s true. I don’t know of any other major museum in the US that has acquired an entire vernacular photography collection curated around a limited number of interwoven themes. Many have acquired individual objects or photograph albums or been gifted batches of snapshots. This acquisition is especially notable because it is a collection made up of thousands of images and objects collected over 30 years by two women!

And, yes, absolutely, I think there will be more acquisitions in future, as vernacular photography is moving front and centre. More artists are using analogue processes and vintage photos in their work, and there is a noticeable increase in programmes and publications focused on vernacular photography in academic and arts organisations (including archive projects such as yours!). Major museums are beginning to collect more vernacular material, and during this unparalleled time of pandemic, people are spending more time online looking at other people’s pictures from the past.

All of this combined, and MFAH’s acquisition of our entire collection, bodes well for more museums and cultural organisations recognising the role vernacular photography plays as the record keeper of our personal and broader social histories.

TFM: Did it feel strange parting with such a long-standing collection? Are you still collecting!

BL: It has been a transition, but there is so much to look forward to ahead of us. And yes, I will always be a collector!

Interview by Rachael Moloney

PS: Thank you for the great post about our PhotoMania Collection (Barbara Levine and Paige Ramey Collection) being acquired by the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston! We appreciate your interest! Barbara

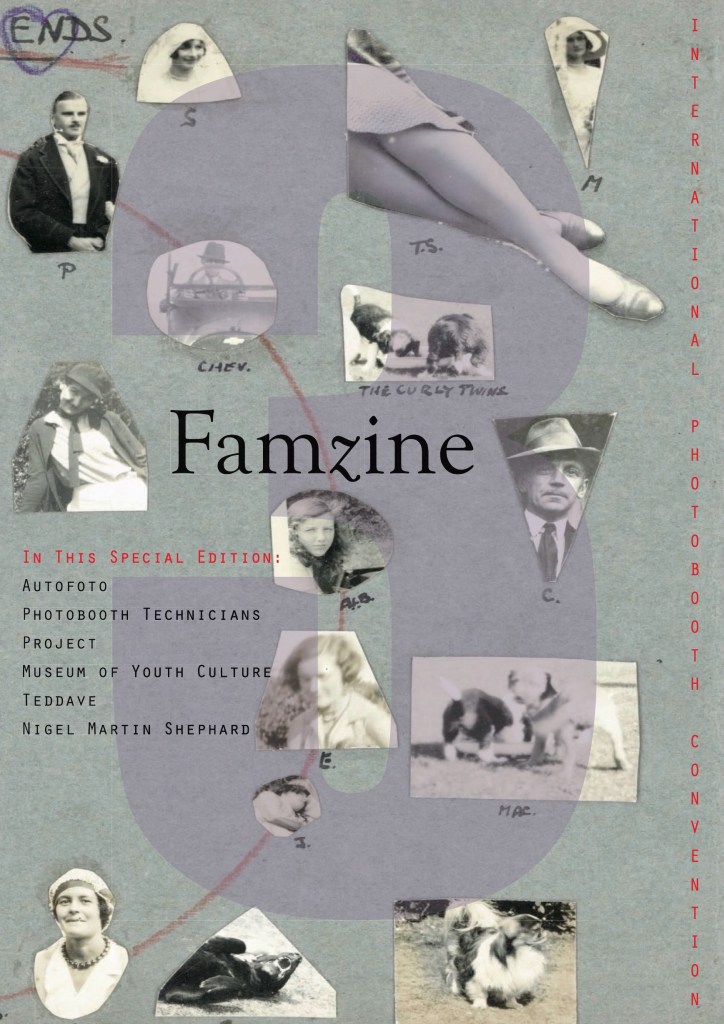

Famzine 3

Produced as a Special Edition in collaboration with AUTOFOTO, Famzine 3 is dedicated to the theme of the photobooth and was published to coincide with the International Photobooth Convention, London, 14-16 July, 2023. In features by AUTOFOTO, the Photobooth Technicians Project, the Museum of Youth Culture, photographer Teddave and Nigel Shephard, we look at the history and legacy of this influential auto-photography machine. We give voice to the dedicated community of people who save photobooths from the scrap heap and keep them running today and consider the personal value that the photostrip holds for those who ventured into the booth, especially in their youth.

If you’d like to order a hard copy of Famzine 3, please get in touch.

Famzine 2

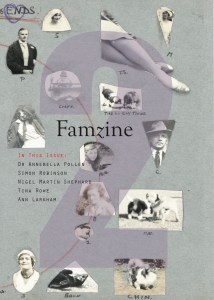

In Winter 2019, to coincide with our launch exhibition Auto-Memento, we were excited to publish the first edition of Famzine, our zine dedicated to vernacular photography. Issue 1 featured contributions by American artist, writer and vernacular photography collector Barbara Levine, British family historian Ben Haslam, Nigel and me, and set the tone for the conversations we want to have around this project.

We’ve now published the second edition of Famzine, in Winter 2022, which you can view on Issuu. In this edition, we focus on amateur family photography’s place within the context of academic study in an essay by Dr Annebella Pollen, Professor of Visual and Material Culture at University of Brighton; the once-popular but almost forgotten phenomenon of ‘walkies’, collected and celebrated by author and publisher Simon Robinson of Easy On The Eye Books; the striking work of artist Tina Rowe; our recent exhibition about tintypes at London’s Art Workers’ Guild; and the research of writer and ‘photogenealogist’ Ann Larkham.

All the contributions to this edition of Famzine signal that vernacular photography is gaining increasing recognition in academic studies, art and curatorial pursuits, and The Family Museum is thrilled to be part of that movement.

If you’d like to order a hard copy of Famzine 2, drop us a line. Famzine 1 is now sold out, but can also be viewed on Issuu.

Famzine

In Winter 2019, to coincide with our launch exhibition Auto-Memento, we were excited to create and publish the first edition of Famzine. Issue 1 features contributions by American artist, writer and vernacular photography collector Barbara Levine, British family historian Ben Haslam, Nigel and me.

Barbara has written numerous books about this niche of visual culture and her photo collages have been exhibited widely (see projectb.com).

Ben is from Norfolk and became a family historian when he inherited hundreds of photographs from his grandparents; particularly beguiling was the visual legacy of his Anglo-Russian relatives. Ben posts on Instagram @william_gerhadie_scrapbook

If you’d like to order a hard copy of the first edition of Famzine, drop us a line.

Rachael Moloney

Book reviews

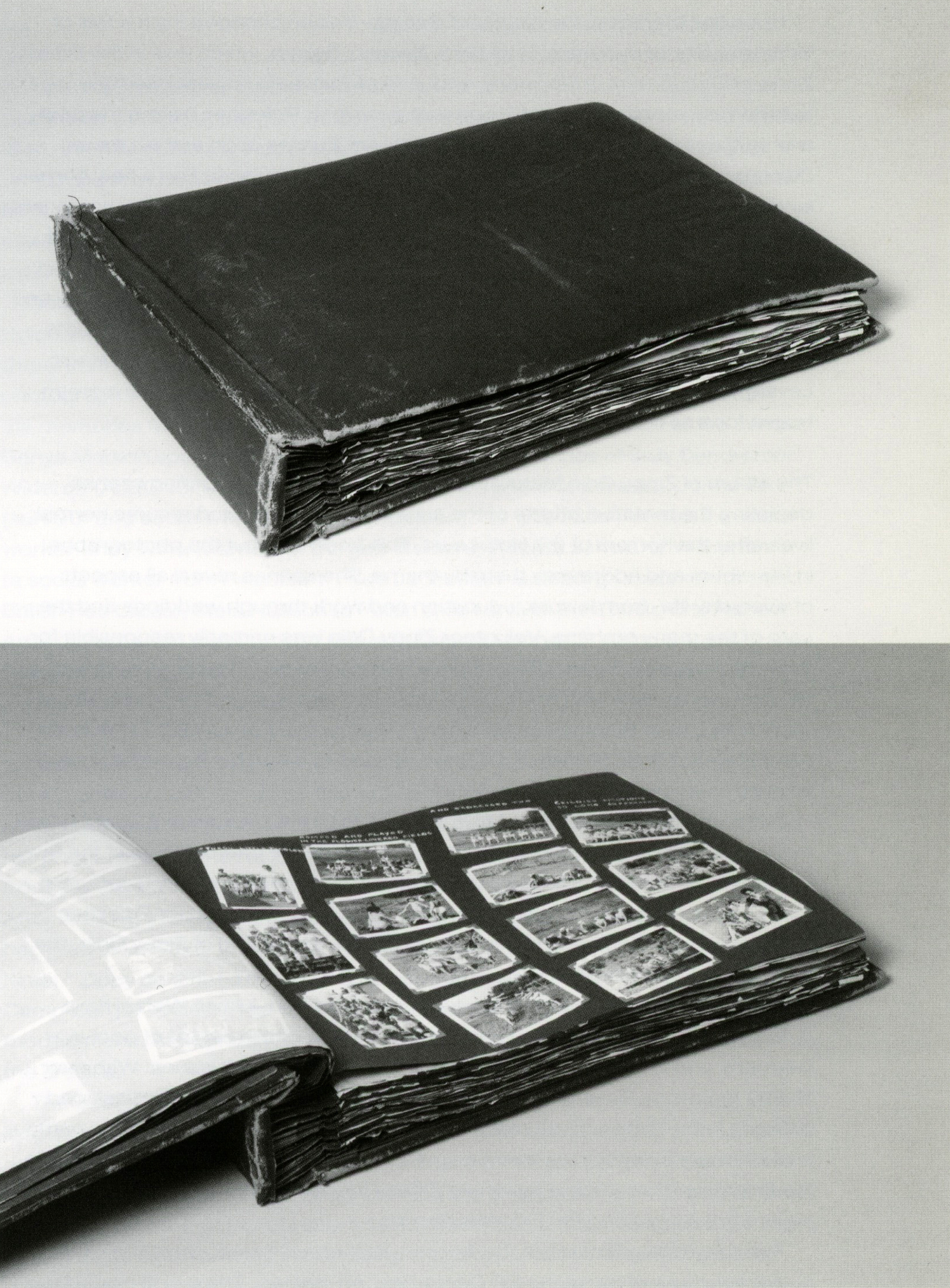

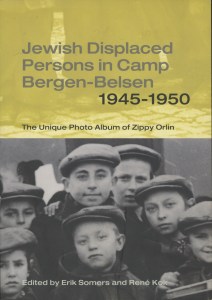

‘Jewish Displaced Persons in Camp Bergen-Belsen 1945-1950: The Unique Photo Album of Zippy Orlin‘, edited by Erik Somers and René Kok (2004, University of Washington Press)

On 19 September, 1986, Chaim Orlin, aged 51, deposited a photograph album at the Netherlands Institute for War Documentation. He was exhausted. It weighed 33lbs and contained 1,117 photographs. He handed over the album and, with only a brief explanation, hurriedly left the building. Once the institute understood the historical importance of the photographs he had given them – it was the largest collection of images documenting the post-war history of the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp – they contacted Chaim for more information, but he had died three days after depositing the album.

The album had belonged to his sister, Zippy. Cecelia ‘Zippy’ Orlin was a Lithuanian Jew, and a naturalised South African, who died in Israel, aged 58, on 1 September, 1980. In 1946, aged 24, she volunteered for the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, known as the ‘Joint’ and established to help the thousands of displaced Jewish survivors of the Holocaust. She was chosen for her fluent Yiddish and worked in the Kindergarten.

Zippy compiled the photo album documenting her experience at Bergen-Belsen from her arrival at the camp in 1946 to her departure in 1948. She took some of the pictures herself but also collected and featured the photos of her friends and co-workers there. Her album is a marvellous piece of archiving. It begins as a threnody to the dead and evolves into a celebration of the resilience of the human spirit and the power of caring.

Soon after its liberation, Bergen-Belsen became a fully organised society preparing itself for aliyah and a school for the re-forging of souls. Historian Hagit Lavsky said of it: ”Life in the camp was a greenhouse for a new Jewish identity.”

Zippy’s inscriptions in the album recount the spirit of a people emerging from oppression:

‘They wanted to live, to provide, to be a child, to play, to keep the law and order, to feast, to celebrate and to care for the soul and body…sturdy little toddlers romped and played in the flower-covered fields and expressed the childish emotions so long suppressed…by love, tears make way for joy, crying makes way for singing, repression makes way for expression’

From the photographs and inscriptions, it is clear that Zippy understood her moment in history. She spent her last 20 years in Israel, where there would have been ample opportunity to donate such an important historical document to numerous archives, but she chose to keep the album her entire life for her own pleasure. Zippy never married; perhaps this was her family album.

Nigel Martin Shephard