This year The Family Museum has been digitising our large collection of standard 8 and Super 8mm films. The collection can be viewed Here:

An archival project about family photography

This year The Family Museum has been digitising our large collection of standard 8 and Super 8mm films. The collection can be viewed Here:

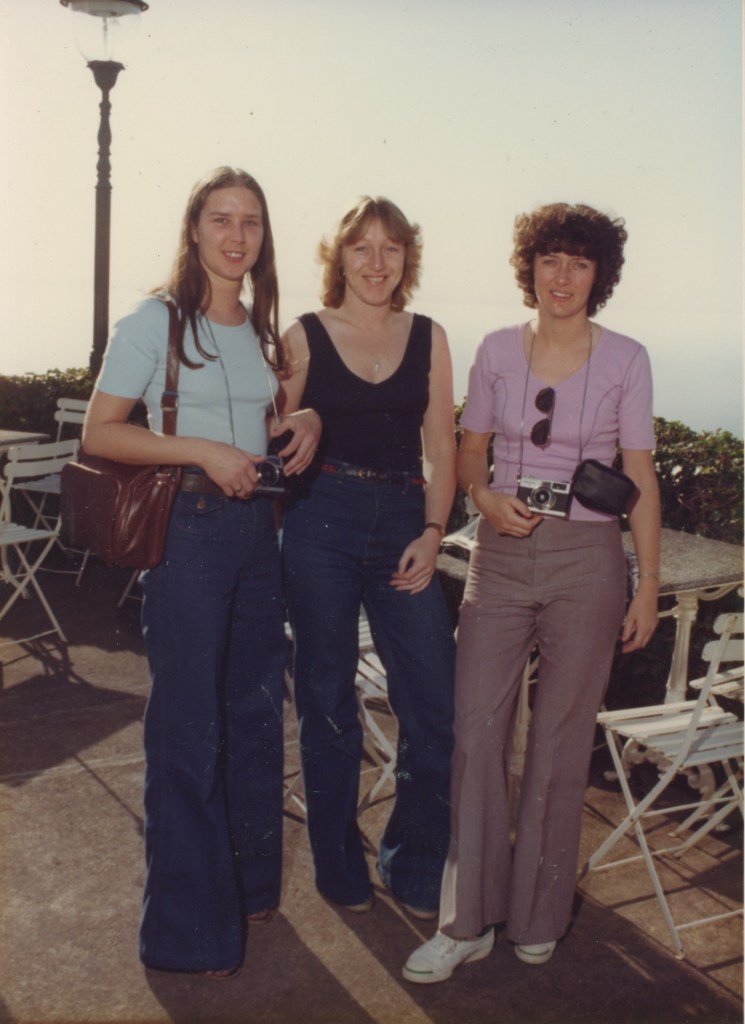

In the mid-1970s, three women in their twenties decided to treat themselves to a Mediterranean cruise ship holiday. They sailed with the Fred Olsen Lines ‘Winter Cruise Club’ aboard the M. S. Blenheim, which began its service in 1970, and weighed 10,427 tons. These souvenir photos were taken by a professional photographer working for ‘Onboard Services’. How long this cruise was and exactly where they sailed to is unclear, but they certainly docked for a while in Madeira. Every activity they ventured into seems to have been punctuated by a drinks party.

Cruise lining, always associated with luxury, can be traced back to the beginning of the 19th century, and the first purpose-built pleasure cruisers began production in 1900 – the first swimming pool was installed on a liner in 1907. The 1950s saw the introduction of lavish entertainments and star turns. Cruiser liners now also boast surf simulators, planetariums and racetracks. Fred Olsen Lines was founded in Norway in 1889 and is still running today. The television series Love Boat, which ran for nine years from 1977 to 1986, helped to popularize the concept of the cruise liner as an opportunity for romance.

Something that one cannot tell from these photos, but which I was able to easily tell by looking at the collection they come from, is that the woman with the dark perm’ and the woman with the blond ‘flick’ haircut were lovers.

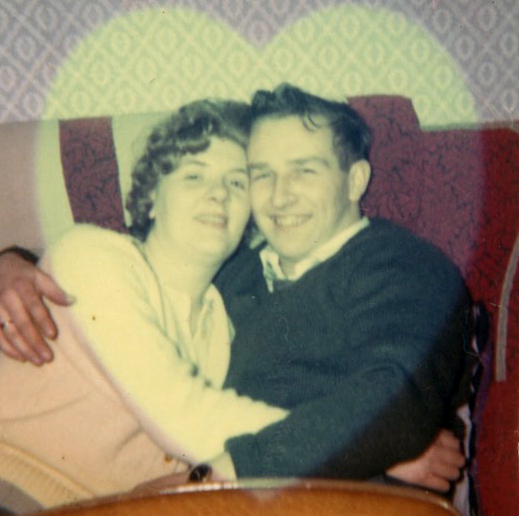

Photographer’s studios, like any business, have to innovate to survive. Over the years they have come up with all manner of gimmicks and offers to attract the weary eye. The photographer’s studio here offered a rudimentary superimposed, photo collage technique that could place a treasured photo of a loved one in the shot too.

This photo dates from the 1940s, and shows a soldier, with a bone china complexion and slightly sun burnt nose, writing a letter home. With pen in hand, he looks up longingly from the page for a moment, where his eye-line meets the image of his beloved wife and child, backlit and inset. Although this image may look a little saccharine now, no doubt when it was received, it melted hearts.

Nigel Martin Shephard

About a decade ago, a friend of mine bought a house in Hemel Hempstead. When she took occupancy, the adopted son of the deceased couple who had lived there had removed almost nothing from the property, including the family’s photos. There were about 100 images in all. Many were, or had been, in frames, including this one. When I saw it, I was thrilled. There was something magical to me about the way the light had played on this image, twice. Firstly, for a fraction of a second, then secondly with a much longer exposure time of perhaps 40 or 50 years, leaving this heart-shaped spotlight on our happy couple.

Nigel Martin Shephard

This album was compiled by a woman in her early 20s, known throughout as ‘I’ or ‘me’. It covers about three years between 1964 and 1966, apart from two photos, and includes her mum, dad, brother and sister, ‘Phillip and Jeanne’, ‘Gran’ and ‘Granddad, and the dog ‘Major’. Most of the album is of peer-group photos.

In albums made by people of this age, a person’s partner can change from the beginning of the album to the end. In 1964, she was with ‘Arthur’ in Margate. By 1966, she had upgraded to ‘Gordon’ and Brixham. ‘Tony’ makes an appearance somewhere in the middle. On the inside cover is a photo of her American penfriend, the preppy-looking Diane Olson. There are two professional black and white souvenir photos, entitled ‘Vestrics Xmas Dance 1967’. In one of the shots there are 16 people sitting at a table full of drinks. The woman beaming most brightly for the camera (top right) is the shutterbug who compiled this album. I think they lived in Arlesey in Bedfordshire, near Letchworth Garden City. The boating shots were probably taken on Arlesey Moat. There is a lovely POV of ‘Maureen’ coolly lounging back at the bow of a rowboat, her pleated skirt dappled in muted sunlight.

This album highlights to me just how available interior photography was to the amateur in the 1960s than in former decades. I particularly like the shots inside the holiday chalets. I wasn’t sure whether flash had been used until I saw it bouncing off the painted wooden door.

Flash photography was introduced first as individual bulbs, optionally mounted on the top of the camera, and then, from the mid-1960s, as flashcubes, and in the 1970s, flip flashes. Flashcubes were enclosed transparent cubes with a flash bulb on each vertical face, which would rotate as each was spent. Once a flash had ‘gone off’, the flashcube could not be touched for about 10 minutes, because it was too hot. Just about every member of my family burned themselves on a flashcube during the 1960s.

Nigel Martin Shephard

Of the countless of albums I have viewed, one thing they share most predictably, along with their common domestic themes, is the psychological focus of the photographer. Rarely in a family album can one see, except in their most rudimentary form, the artistic consideration of, say, framing, composition, perspective or atmosphere, let alone symbolism or metaphor. There are comic tableaus sometimes and some curious set pieces, but rarely anything consciously artistic. Rather, the photographer’s sole focus is normally on the person with whom they have a relationship and to whom they are attached. As long as their favoured or loved one appears in the shot, the rest is largely insignificant. Yet in most family albums, due to a confluence of chance circumstances, there is often one photo that can be described as ‘artistic’.

Throughout this entire album compiled in the 1960s, there is no sign of any artistic flair. Most are poor photographs of dreary scenes, making this one stand out. The first thing that gives this photo its immediate allure is that there are three clear picture planes: the woman and the bag in the foreground, the bench and the bin in the mid-ground and the buildings in the background, drawing the eye in and giving the image perspective. Although the horizon is sloping (the first thing likely to be fixed by the artistic eye), it splits the frame nicely too. It’s late afternoon; the sun is low in the sky. Long shadows have given the image depth; the fading day and muted sunlight have softened the image. How do we know that these were not deliberate artistic decisions? We don’t. But certain other features make it unlikely.

The vertical centre of the frame runs between the bin and the woman sitting reversed on the bench – this empty space seems an unlikely subject for a photo. As she puts on her shoes, the woman in the foreground brings narrative to the moment. Seen in candid motion, she is clearly not posing for the shot. The man on the bench with his back to the camera adds a little mystery to the scene. The Adidas bag anchors the composition and dates the image, but its position in the frame is not central enough to assume it as the subject of the photo. I believe the photographer was inspired to take a picture of the woman on the bench. Out of focus and also caught in motion, she is the only person in the shot facing the camera. If she were the subject, then in this regard the photo is an abject failure, but the overall effect is an artistic success.

Nigel Martin Shephard

“Europe presents a live picture of a warming world and reminds us that even well prepared societies are not safe from impacts of extreme weather events.”

Petteri Taalas, Secretary-General, World Meteorological Organization,

2016–present

One thing that 2022 is likely to be remembered for is being the year in which climate change became a materially conscious reality for the world’s wealthier nations. Up until the 1970s, most people were unaware of environmental concerns, and it was not until the 21st century that claims of global warming finally passed through all three stages of truth: firstly they were ridiculed, secondly they were violently opposed, and now they are accepted as self-evident fact. It is sobering to think that, in the UK, 2022 was the hottest year on record, marginally beating 2014!

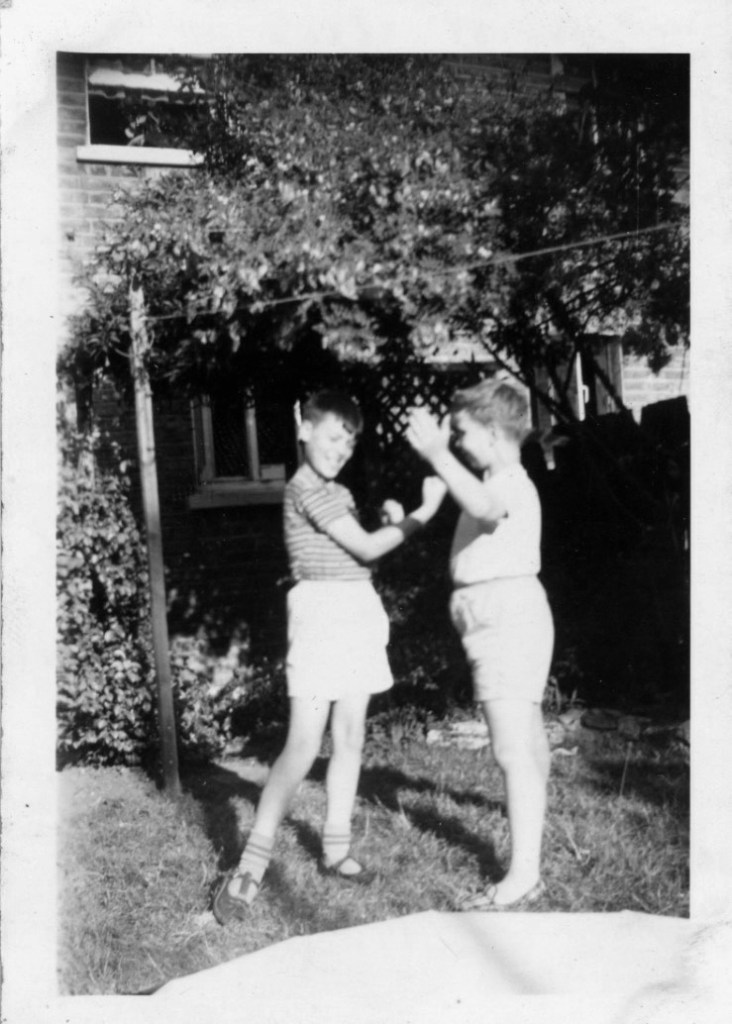

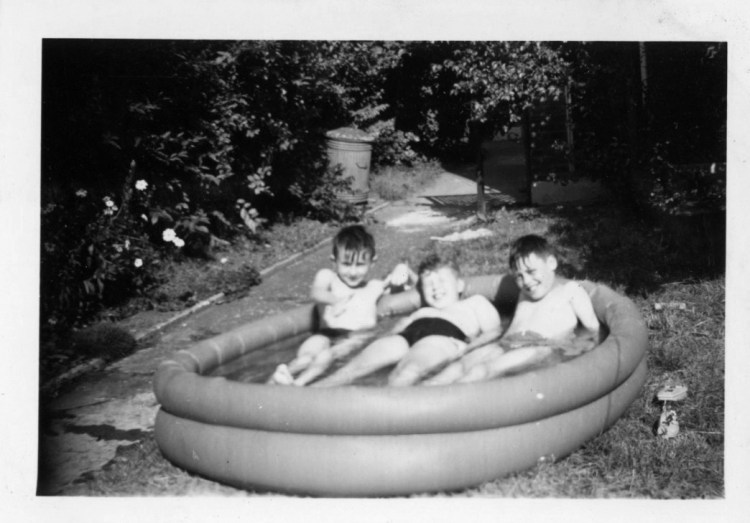

From this perspective, these photos, and many others in The Family Museum archive compiled through the 20th century, prompt me to think about how attitudes have changed over time. Viewed through the neo-puritan lens of the 21st century, these images begin to take on a different mood. They start to tell a story not simply of holiday gaiety and abandon, but also a story now seen through a veil of lost innocence – environmental catastrophe-anxiety was unknown to people of the last century; nuclear-annihilation anxiety, perhaps, but the sun meant only good times. Now we need to be wary of the heat, cold and wet as possible harbingers of calamity. The photos featuring summer holidays in our archive illustrate an attitude towards our environment that is no longer as easy to muster – each is a time-weathered snapshot of a certain carefree past.

Nigel Martin Shephard

Many of the significant events, milestones and rites of passage in our lives are marked by photographic commemorations. Christenings, birthdays, weddings and anniversaries all appear in family albums with comforting regularity. Yet family albums can also record more intimate moments, which are no less common.

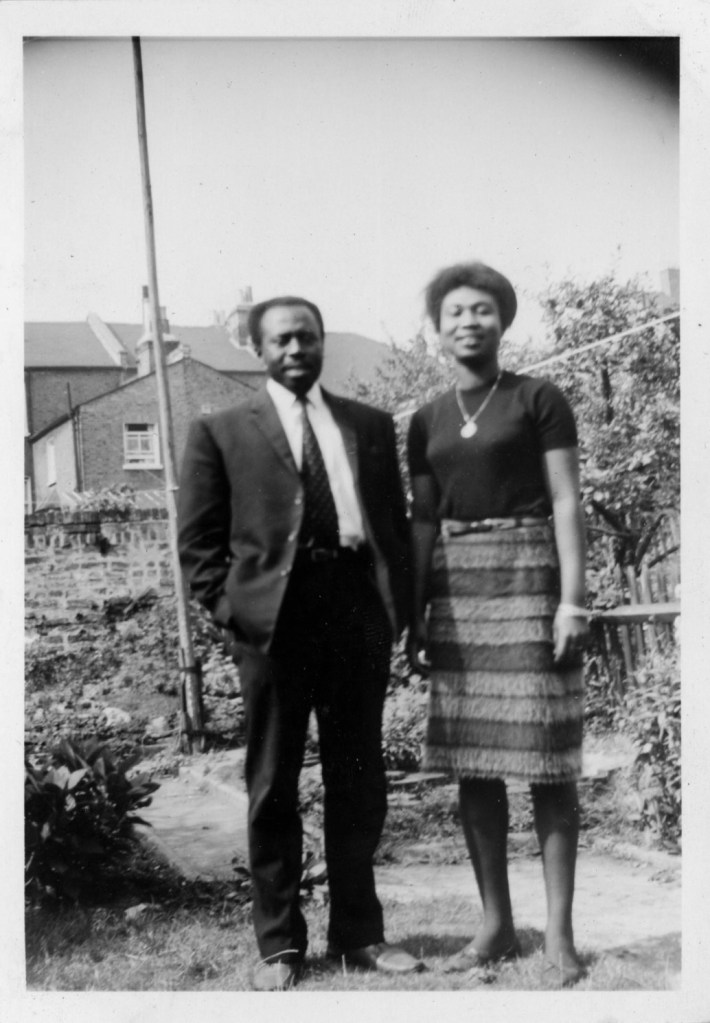

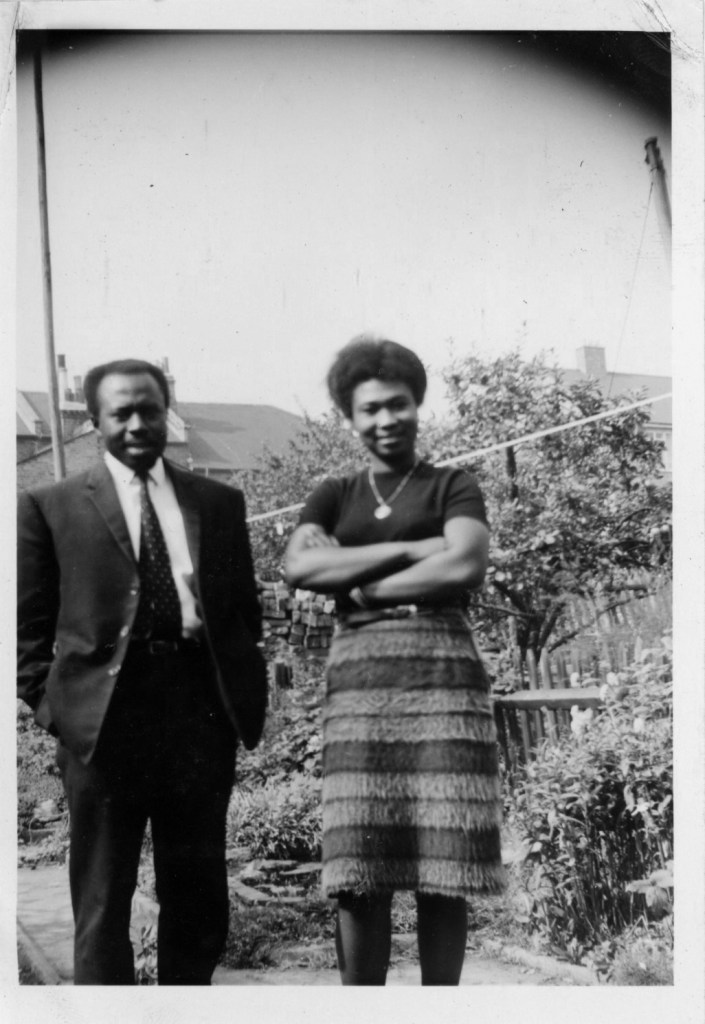

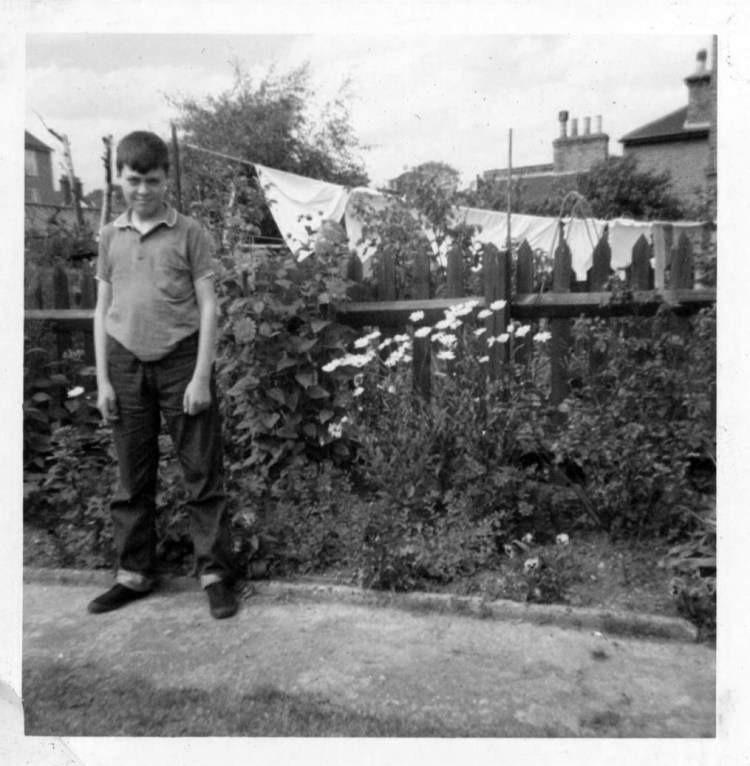

This photographer is a 13-year-old boy. Albums compiled by people this young can often be a combination of admirably untempered enthusiasm and slipshod technical know-how. There are shots of wildlife and his friends and family in the back garden; an out-of-focus Sooty the cat gets two or three pages, nine photos in all. There is a Christmas tree piled high with presents and ‘Aunty and Uncles Silver Wedding’, both events transcribed in colour; and a boat trip to Paris and back, in black and white. Curiously, two photos of a very homely looking West Indian couple, ‘Mr and Mrs Kufore, 1963’, make an appearance in the middle.

There are six photos spread across three pages, which appear under the heading: ‘Last day with the Foxe’s (before they moved), 1966’. David Fox was the photographer’s friend. The earliest photos of him in the album are dated 1963. They chose to spend their last day together in central London, among other things, feeding the pigeons in Trafalgar Square, once a must-do ritual during any day trip to the capital. They may not have had to travel far, as in one photo the photographer is shown wearing his ‘42nd Greenwich Scouts Uniform’. They took a boat trip down the Thames, viewed Cleopatra’s Needle and visited Westminster Abbey, where the Foxes and their mother were photographed in the Cloisters. In this shot, the way David looks up at his mother seems to implore.

These photos reminded me of my own experience of having a childhood friend move away, particularly the feeling of powerlessness. I met Troy Swain at the recreation ground, as we commonly did. We sat on the roundabout not the swings, a sign of the gravity of the conversation. He told me they were moving away because of his dad’s job, and he didn’t want to go. I don’t remember where they were moving to – it might as well have been Andromeda because we both knew we would never see each other again.

Nigel Martin Shephard

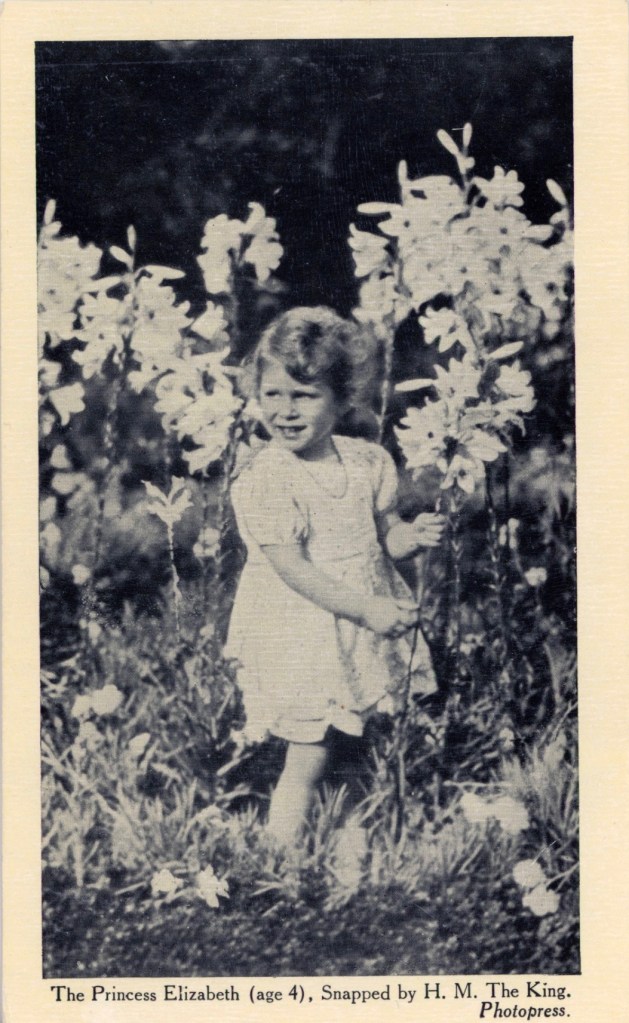

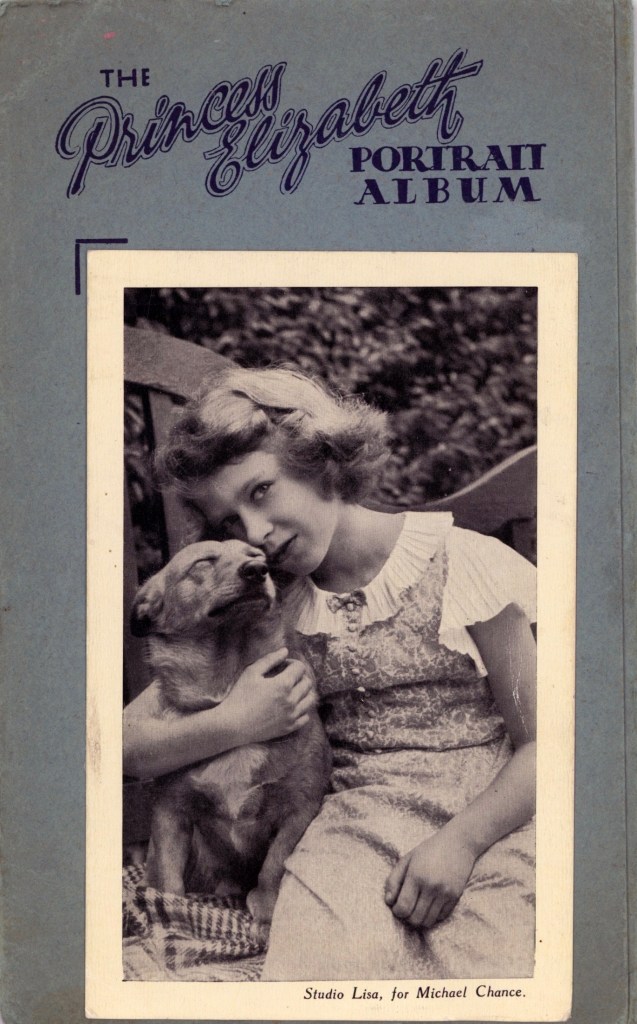

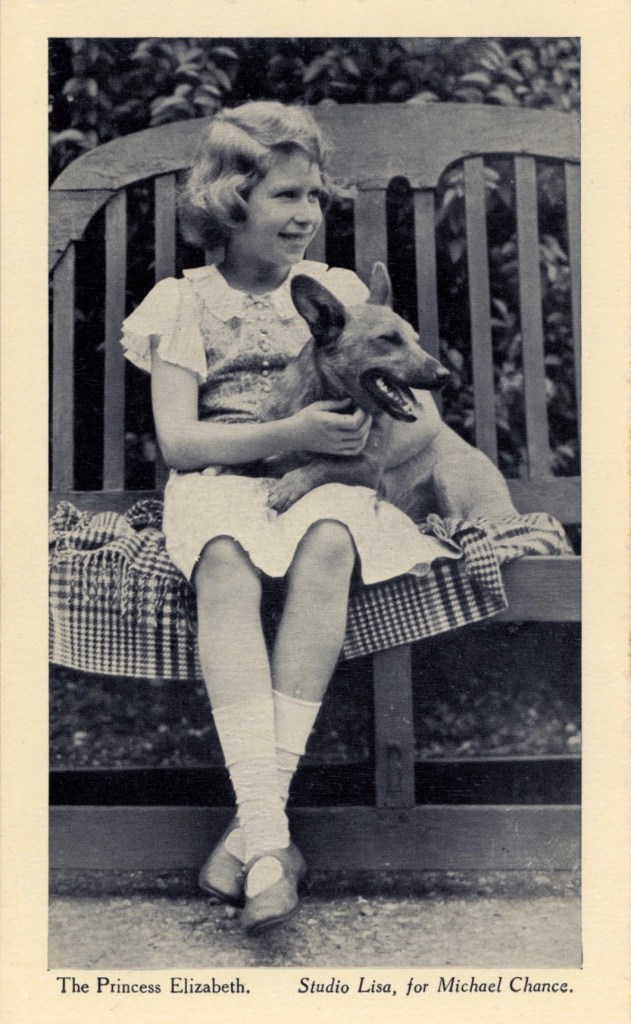

It would be sad to let the death of Queen Elizabeth II pass without paying some small tribute – she had been on the throne all my life. This set of seven photos was published as a supplement in the magazine Welcome Weekly in 1952, the year of George VI’s death and Elizabeth’s ascension to the throne. They come in a folder similar to a photo-negative envelope. On the inside cover the editor writes:

‘The Princess Elizabeth was born on 21st April, 1926, at 19 Bruton Street, London, the town residence of her grandfather, the Earle of Strathmore.

‘Her other names are Alexandra May. The princess has a distinctive personality, and although Fate has called her to a high destiny she is still the unspoilt and lovable child who has won all hearts.

‘These photographs are presented to you with the gracious permission of Her Majesty the Queen, and they will, I know, be long treasured in your home.’

When trying to write about the Queen of England, one struggles to separate the person from the wealth and power. But issues of Royalist versus Republican are not the concern of this blog. For me, the Queen’s death represents something more profound: the symbolic passing of a generation’s values. Those who were alive during WWII are now almost all dead. John Cruickshank (102), John Hemmingway (103) and Johnny Johnson (100) and others, still survive at the time of writing but we can safely say that, sadly, they too will soon pass.

The war generation faced hardship, heartache and horror. Yet the war also brought the opportunity for new experiences and personal growth. The Queen herself, working for the Territorial Auxiliary Service, became a competent ambulance driver and motor mechanic, skills and interests she held all her life. My own mother was hardly more animated than when she was waxing about her war work as a metal-lathe turner – she had wanted to join the Women’s Land Army, but her father’s service in WWI had left him with a loathing of uniforms, so he forbade them in the house.

My father fought during the war. He was stationed in Africa. Born in 1913, he was a coal miner from Burnley called up to serve. As a child, I wanted to hear his war stories, but he knew I was too young. By the time I was old enough, the war, for him, had passed into history. It must have been quite something for ordinary working people to be thrown into such demanding and exotic locations under such dramatic circumstances. In the 1940s, for someone of my father’s background it was doubtless extremely unusual to meet, spend time and form bonds with Africans. A friend had to point out to me that this might have had a greater influence on him than I had considered. Through the 1960s my father and mother, both now dead, fostered around 60 children, almost all of them Afro-Caribbean. I was one of those children.

Nigel Martin Shephard

On Sunday, 18 September, The Family Museum will be taking part in the Art Workers’ Guild Table Top Museum exhibition in Queen Square, Bloomsbury, London. We plan to display our comprehensive collection of tintype photographs, so I thought this would be an ideal time to write about one of the rarer photos that we have in our archive.

Scholarship on the tintype trade is scant, but in the most informative essay written on the subject, Cheap Tin Trade by Audrey Linkman, the author writes: ‘ The ferrotype lingered on in Britain to finally resign a very frail and tenuous hold on life in the early 1950s – a centenarian! ’

Other sources have cited a later date, but regardless of the exact timing of the industry’s demise, this simple shot of a little boy on a beach holiday, taken by a commercial seaside photographer, is the most modern tintype I have seen, by far. It comes from the same peer group album as the photos in my Coin-op Diary blog. All of the images in this collection date from the early to mid-1960s. At first I thought this image was also from this era, but I now think it more likely to date from the late 1940s or 1950s.

The traditional flaw in ferrotype photography – the technical name for tintypes – had always been their dullness and lack of fidelity by comparison to their paper and glass counterparts. Yet none of these problems are present in this photo; it is as bright and clear as any of its contemporaries. It seems a shame that the tintype trade ended just as it looked to have conquered its major aesthetic challenge.

See you on the 18th…

Nigel Martin Shephard