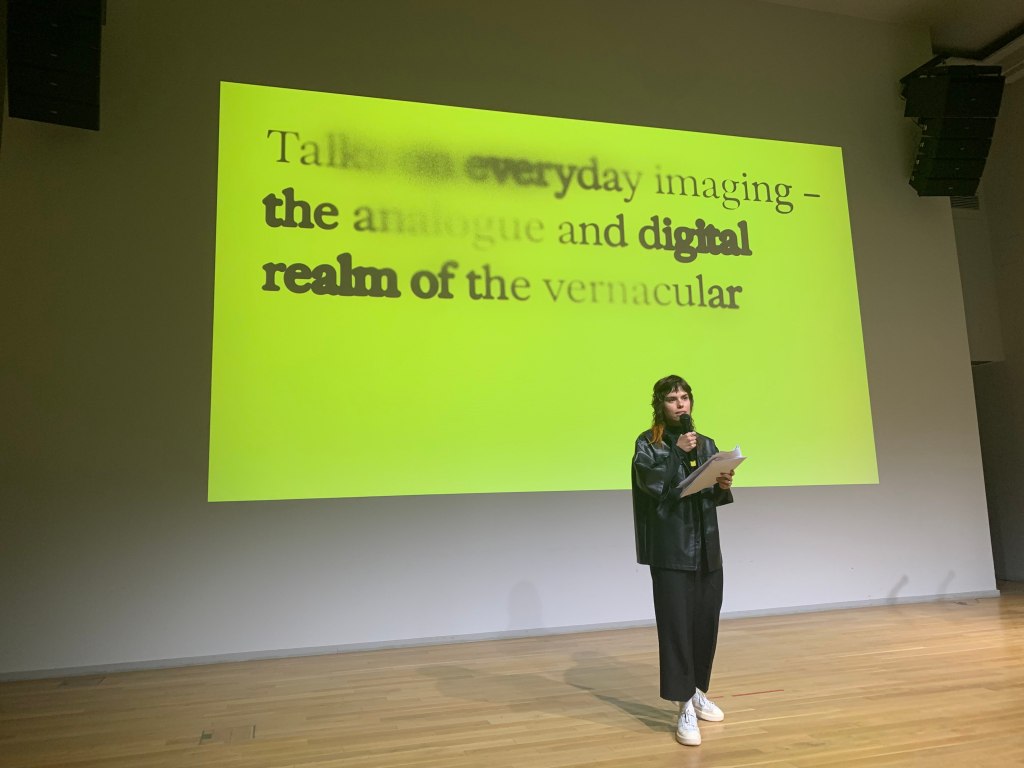

‘Talks on everyday imaging – the analogue and digital realm of the vernacular’

02.11.23

Eidolon Centre for Everyday Photography, Budapest, Hungary

On 2 November, The Family Museum was invited to speak at the conference ‘Talks on everyday imaging – the analogue and digital realm of the vernacular’ in Budapest. The event was organised by the newly formed, Budapest-based Eidolon Centre for Everyday Photography and was hosted at Moholy-Nagy University of Art and Design. Nigel gave an outline of our project and work in the family photography niche and a moving account of the importance of family photos to his own relatives.

International academics, critics, curators and artists, our fellow speakers (Geoffrey Batchen, Michal Simunek, Lukas Birk of Fraglich Publishing, Judit Gellér, Miklós Tamási of Fortepan, Sándor Kardos, Annebella Pollen, Joanna Zylinska and Joachim Schmid) ranged far and wide in their talks, from analogue-digital encounters in photography (Michal Simunek) to Hungary’s history of researching vernacular imagery (Judit Gellér) to mass photography (Annebella Pollen) and the future of photography itself (Joanna Zylinska).

Ahead of the event, I interviewed Eidolon’s founding Director, Róza Tekla Szilágyi, to talk about the origins of the Eidolon Centre and its mission to promote the importance and relevance of vernacular imagery in Hungary and beyond. Róza also interviewed Nigel and I for the excellent Eidolon Journal.

We were thrilled to be included in Eidolon’s debut conference and inspired by the people we met. Hopefully, this is just the beginning of a much wider discussion about the relevance and importance of vernacular photography in all its guises.

Rachael Moloney

100 Tintypes: Artists and Hustlers

18.09.22

Table Top Museum, The Art Workers’ Guild,

6 Queen Square, London WC1N 3AT

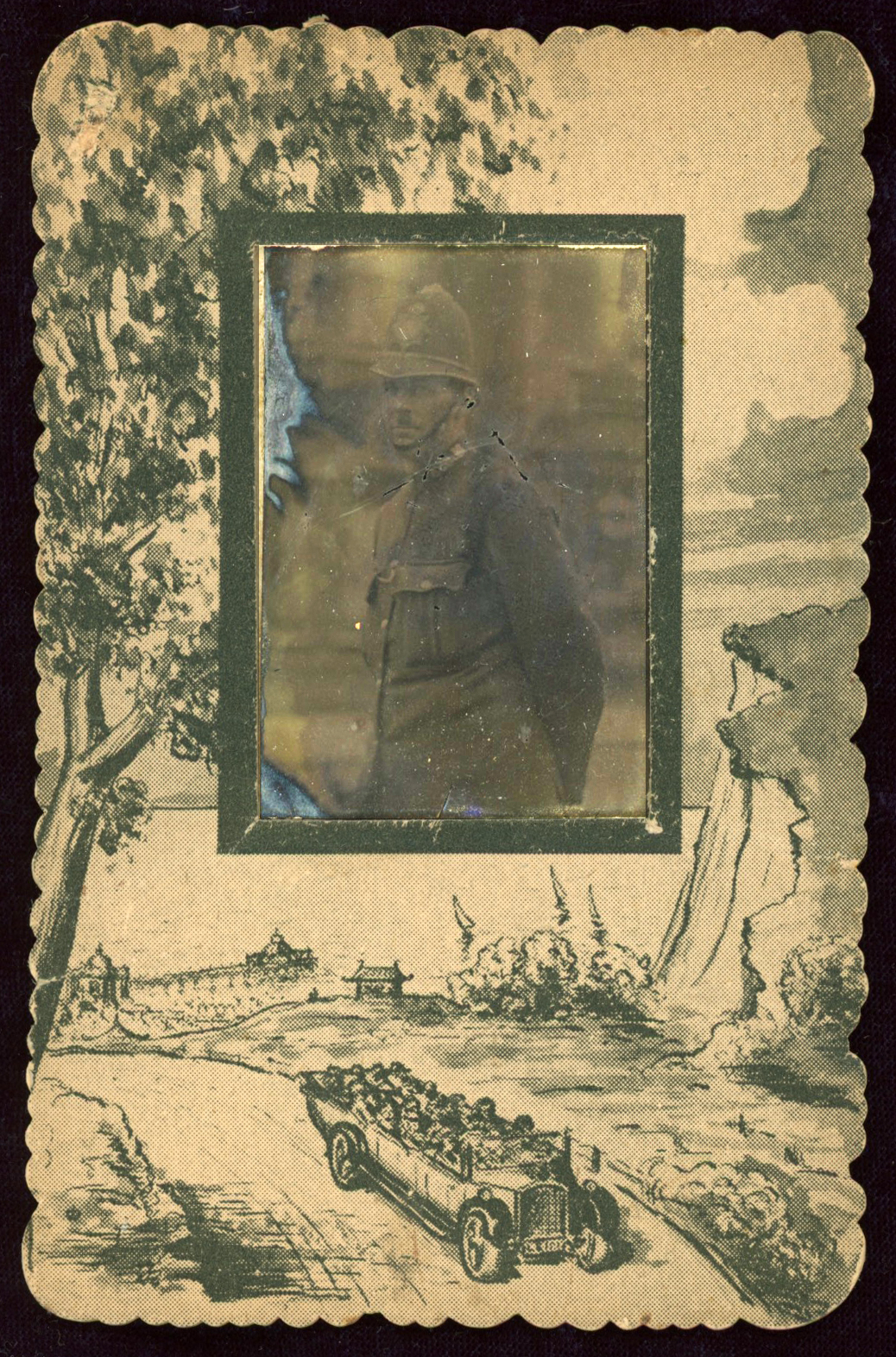

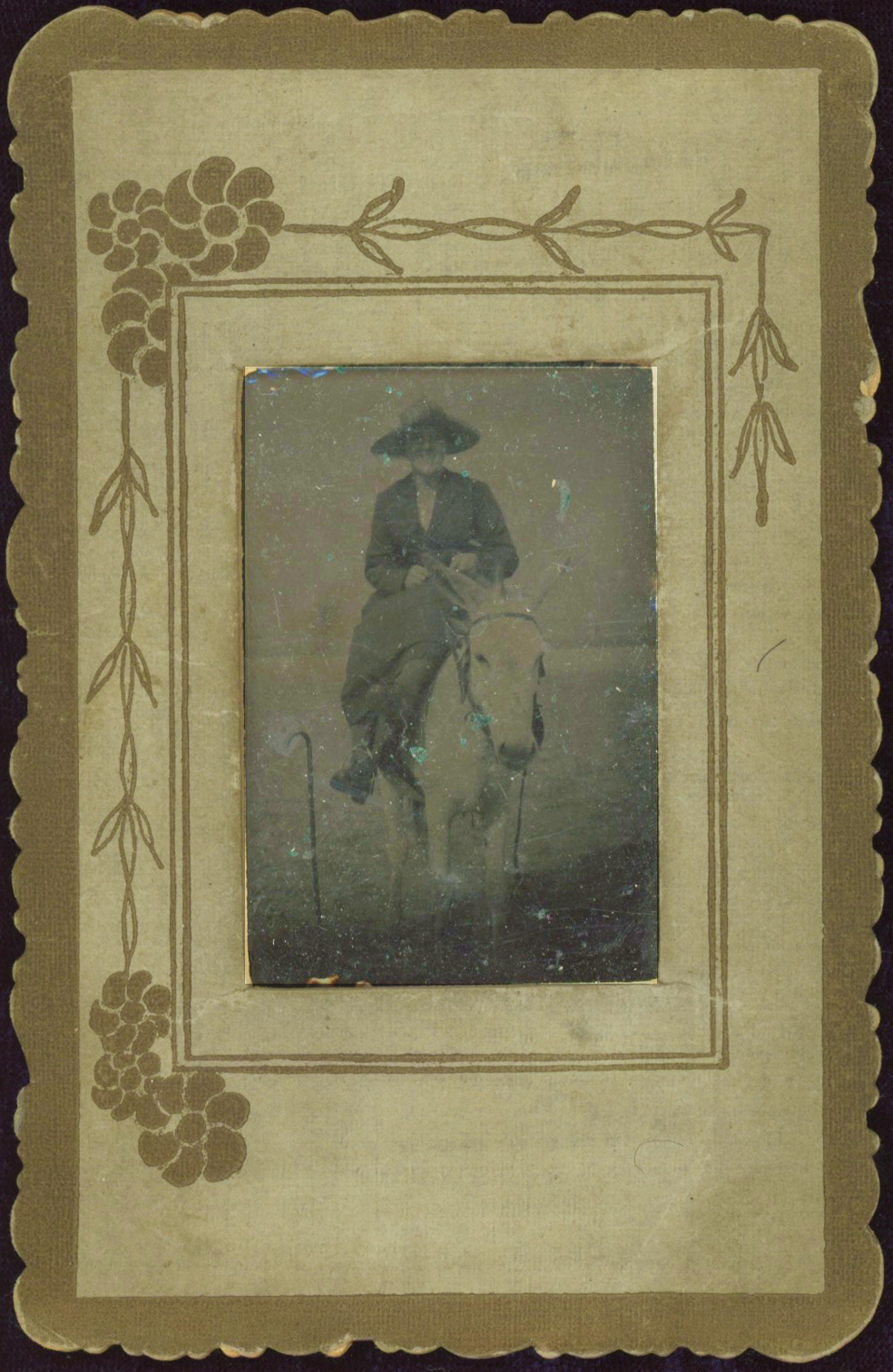

Tintype photography trod the same path as all early Victorian photography, leaning at first on painting for its credibility and courting the wealthy for its patronage. Yet the simplicity and swiftness of the wet collodion process used to produce tintypes, and the cheapness and durability of the metal ferrotype plates that formed their substrate, meant that a diverse pool of non-professionals could take up photography, in locations far flung from the well-appointed studio.

With little technical know-how needed, the tintype trade was open to any chancer or adventurer entering the field. This new kind of operator took their inspiration not from the world of art, like photography’s early practitioners, but from the shady commercial world of street hawkers, peddlers, showmen and carnies. Advertisements for tintype cameras could read: ‘Requiring no skill to operate’ and ‘A good way of clearing depts’. In the minds of most people, this new breed of photographer occupied the lowest rung of society, and it must have been galling to professional studio owners that their most respectable patrons would indulge in the inferior work of ‘bunglers’ for novelty.

The tintype found its most successful commercial expression in the American Gem. Less than an inch square, these portrait photographs, mounted in decorative papier mâché frames, could be bought in high-street studios by the score for less than a penny each. Gems were extremely popular throughout the latter decades of the 19th century, but towards the turn of the 20th century, the work of the itinerant photographer, who could pitch their makeshift studios in any bustling spot, was becoming more visible.

Throughout the Victorian era and well into the 20th century, the cheap day rail or coach excursion was an extremely popular sojourn for cash- and time-strapped working people. These day-trippers, looking for entertainment and cheap thrills, proved fertile customers for the while-you-wait tintypists, and provided the sales traffic needed for a businesses working at the edges of profitability. Tintypes could be produced in a matter of minutes, and were the ideal inexpensive and fun memento of a good day out.

One unique and favourable aspect of ferrotype photography, which is rarely mentioned, is that many of these cameras had a very shallow depth of field, sometimes as little as one inch. In the right hands, this can result in extremely intimate and absorbing portraiture – a feature exploited by the many contemporary and hipster tintypists who have opened boutique studios across America and Europe in the past decade. The tintype has once again regained its art status.

The Family Museum will be exhibiting its latest show, ‘100 Tintypes: Artists and Hustlers’ at The Art Workers’ Guild Table Top Museum event, 18 September 2022, 11am–5pm, The Art Workers’ Guild, 6 Queen Square, London WC1N 3AT.

Nigel Martin Shephard

Whitsun Tides: A British Bond with the Sea

29.05.22–30.06.22

Launderette, 88 Stoke Newington High Street, London N16 7NY

How should we display pictorial representations featuring and created by the people, which are engaging, moving, enlightening, thrilling, funny, sad, puzzling, embracing and sublime, when they have no easily located place in the discourse of our aesthetic and intellectual life? In recent years, numerous parties have been asking this question in different ways, particularly with regard to amateur family photography.

Starting with this Whitsun Tides show, The Family Museum has planned a series of exhibitions in spaces not normally associated with art. This first exhibition is on now at the Launderette, 88 Stokenewington High Street, London.

By placing these images in settings outside the conventional gallery space, we hope to make a contribution to the debate about found family photography’s appropriate place in our culture.

All of the photos in this exhibition are housed in bakelite contact printing frames, which come from ‘home photography kits’ made by the company Johnsons of Hendon, they date from the 1950s.

To find out more about the photographs in the show, scan the QR code in the gallery above.

With many thanks to Andy and all the staff at the launderette.

Auto-Memento: Stickyback Photography + The Family Museum Archive

23.10.19–04.01.20

Swindon Museum & Art Gallery

Our debut exhibition at Swindon Museum & Art Gallery was a hit. Almost 3,000 visitors attended the show, many of whom commented that after viewing the show they were inspired to get out their family albums currently hidden deep in their loft or under the bed. We were interviewed by two local radio stations, BBC Wiltshire and Swindon 105.5, at the launch of the show, and enjoyed talking to local journalists about our collection of Swindon ‘Stickyback’ photographs and The Family Musuem project.

Stickybacks were a type of popular Edwardian portrait taken in itinerant studios

in towns and cities across the UK from the turn of the 20th century up to WWI. Pop-ups of their day, these studios were run mostly by self-taught photographers who produced a series of strikingly candid and modern portraits of their customers in strips of six small images with a gummed back, hence the name ‘Stickyback’.

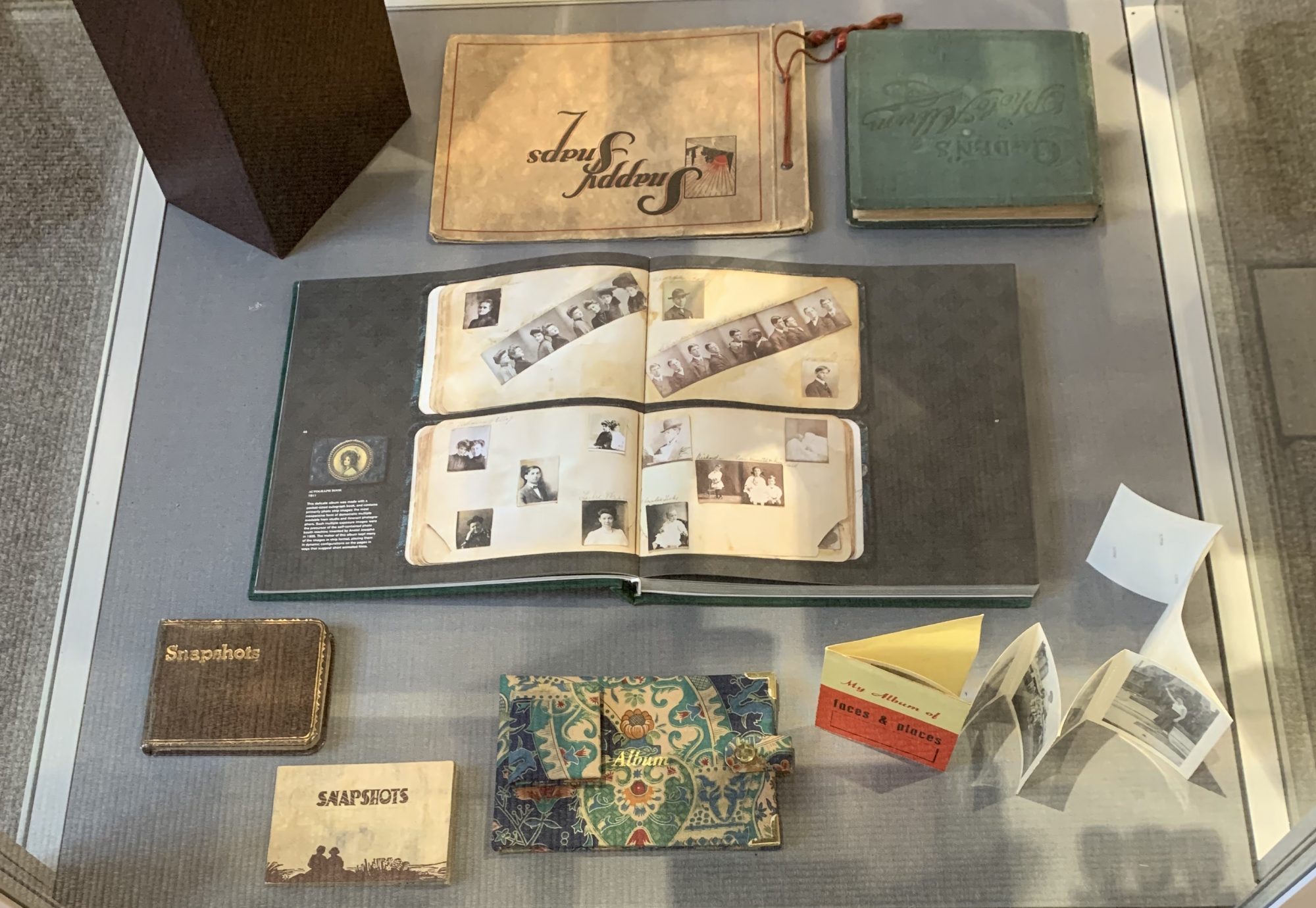

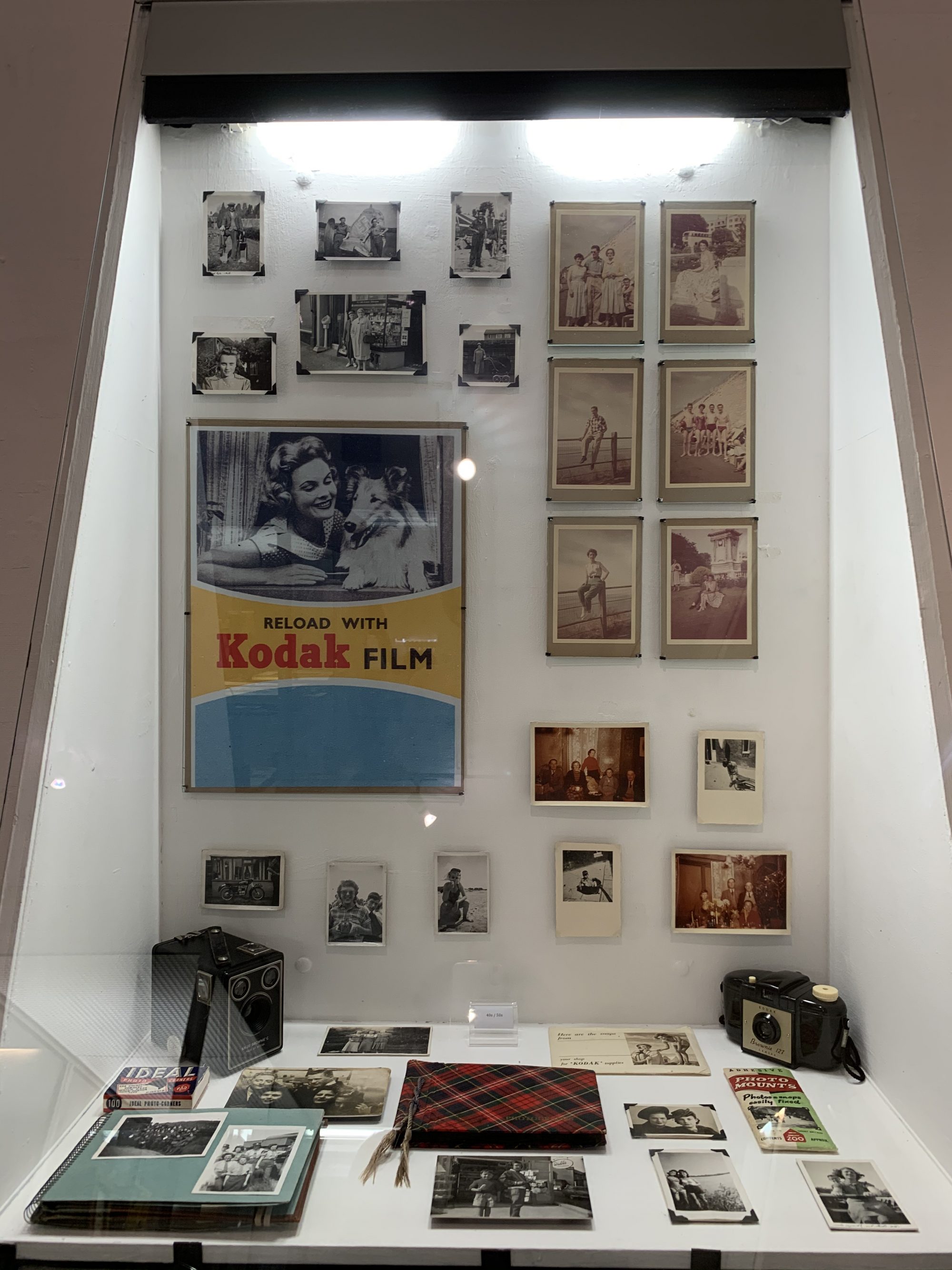

Auto-Memento featured a set of 72 of these photographs taken in a studio located at 15 Regent Street, Swindon, sometime between 1906 and 1912. Many of the subjects returned to the studio several times to have their photo taken, including the young teenage girl shown here. The exhibition was also the official launch of The Family Museum project and featured a selection of photographs, albums, vintage cameras and photographic ephemera charting the rise of amateur photography across the 19th and 20th centuries.

Take a video tour of the exhibition here and watch this space for news of future Family Museum events and happenings…