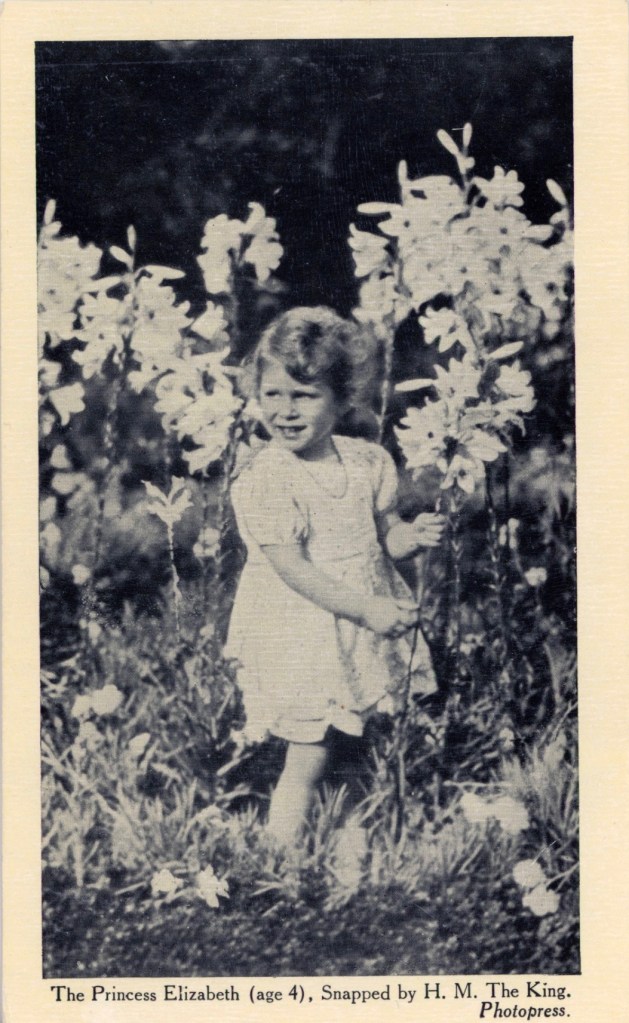

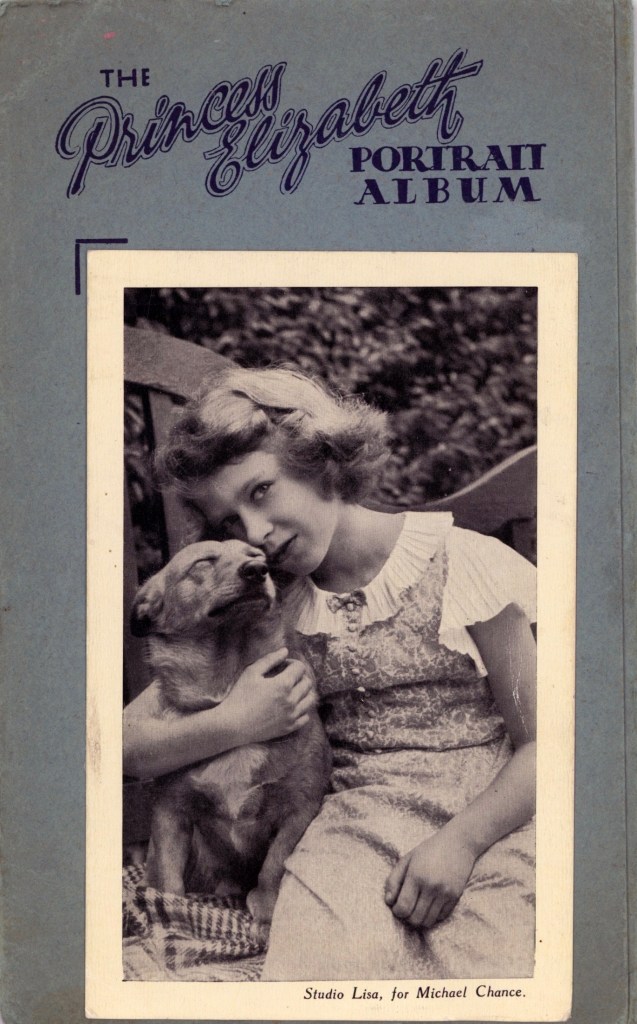

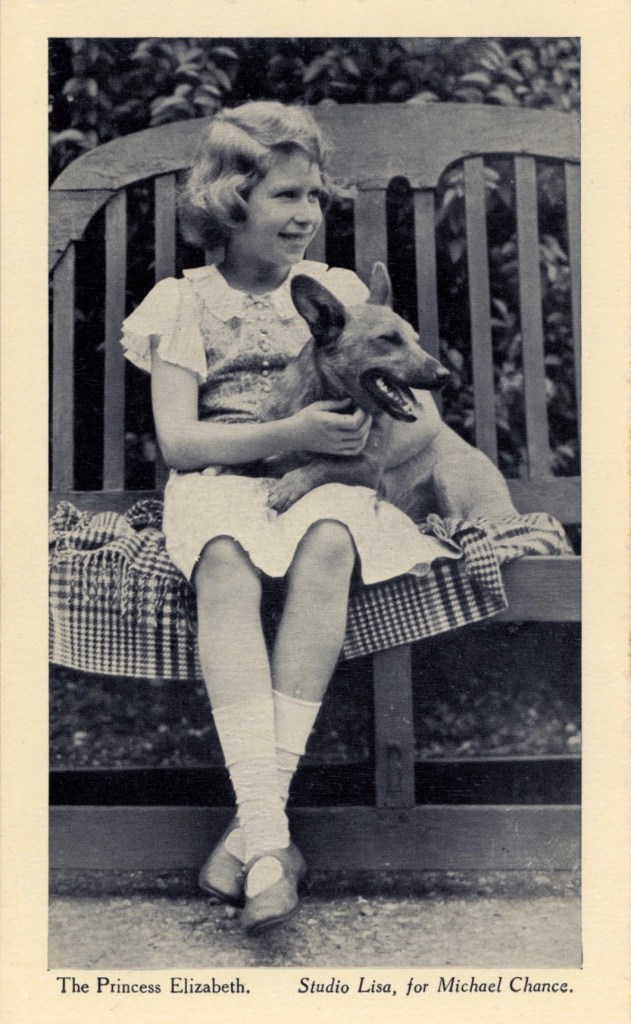

It would be sad to let the death of Queen Elizabeth II pass without paying some small tribute – she had been on the throne all my life. This set of seven photos was published as a supplement in the magazine Welcome Weekly in 1952, the year of George VI’s death and Elizabeth’s ascension to the throne. They come in a folder similar to a photo-negative envelope. On the inside cover the editor writes:

‘The Princess Elizabeth was born on 21st April, 1926, at 19 Bruton Street, London, the town residence of her grandfather, the Earle of Strathmore.

‘Her other names are Alexandra May. The princess has a distinctive personality, and although Fate has called her to a high destiny she is still the unspoilt and lovable child who has won all hearts.

‘These photographs are presented to you with the gracious permission of Her Majesty the Queen, and they will, I know, be long treasured in your home.’

When trying to write about the Queen of England, one struggles to separate the person from the wealth and power. But issues of Royalist versus Republican are not the concern of this blog. For me, the Queen’s death represents something more profound: the symbolic passing of a generation’s values. Those who were alive during WWII are now almost all dead. John Cruickshank (102), John Hemmingway (103) and Johnny Johnson (100) and others, still survive at the time of writing but we can safely say that, sadly, they too will soon pass.

The war generation faced hardship, heartache and horror. Yet the war also brought the opportunity for new experiences and personal growth. The Queen herself, working for the Territorial Auxiliary Service, became a competent ambulance driver and motor mechanic, skills and interests she held all her life. My own mother was hardly more animated than when she was waxing about her war work as a metal-lathe turner – she had wanted to join the Women’s Land Army, but her father’s service in WWI had left him with a loathing of uniforms, so he forbade them in the house.

My father fought during the war. He was stationed in Africa. Born in 1913, he was a coal miner from Burnley called up to serve. As a child, I wanted to hear his war stories, but he knew I was too young. By the time I was old enough, the war, for him, had passed into history. It must have been quite something for ordinary working people to be thrown into such demanding and exotic locations under such dramatic circumstances. In the 1940s, for someone of my father’s background it was doubtless extremely unusual to meet, spend time and form bonds with Africans. A friend had to point out to me that this might have had a greater influence on him than I had considered. Through the 1960s my father and mother, both now dead, fostered around 60 children, almost all of them Afro-Caribbean. I was one of those children.

Nigel Martin Shephard

What a nice post. We were glued to the royal coverage, it’s not that we were serious royal supporters but as you say QE2 was such a fixture of society for all our lives. It’s interesting to hear about your father; my Grandfather went over just after D-Day but would never talk to us about it though we often asked.

LikeLike